A kudu like a statue

July 5, 2016

My first African adventure

July 6, 2016

A discussion on rifles around a campfire has its own dynamics. It is here that belief systems on preferences regarding calibres are created and cemented into near dogmatic truisms. Never dare to challenge these beliefs if you’re not prepared to argue in circles until the pointers of the Southern Cross vacate the firmament and drop behind the horizon. To make derogatory remarks on a beloved rifle/calibre combination has proven a most effective way to put a strain on friendships.

Wherever hunters gather, the quest to identify the ultimate hunting round is on. In the world of global air travel there always seems to be a need to elevate a certain calibre to the golden pedestal of superiority that assures unwavering success under all hunting conditions in the chosen destination.

Exchanges like these certainly spurned the evolution of firearms since prehistoric times, culminating around 1884 in the present phase with the inception of smokeless powder.

This started a transformation of reducing beefy black powder rounds such as the 577 Snider and 577/450 Martini-Henry cartridges in both calibre and capacity. The birth of the French 8x50R Lebel defined new standards in 1886, with additional impetus provided by the creation of the 303 British in 1887 and the 8x57J by Mauser in 1888. A whole family of cartridges evolved around the latter, ranging from calibres necked down as low as 6 mm (eventually down to 5.6 mm) and up to 10.75 mm, using the same case. The venerable 30–06 followed in 1906, which also inspired many modifications to this case design. Most of these calibres encompassed the general doctrine that a heavy bullet travelling at low speed was what a hunter should choose.

There were various high-speed versions available prior to 1940, such as the 220 Swift, 270 Winchester, 300 Holland and Holland Magnum, and those by German designers, such as Halbe & Gerlich, Brenneke and vom Hofe. These cartridges were never properly accepted until Roy Weatherby embarked on a masterful marketing campaign to convince the hunting world that ‘hydrostatic shock’ from high-speed bullets can produce incapacitating neurological effects in animals on impact due to a shock wave transmitted through liquid-filled tissues. He used a slight modification of the existing PMVF (Powell-Miller Venturi Free) bore cartridges with a double radial shoulder and created his own very impressive belted Magnum line-up to support his theory.

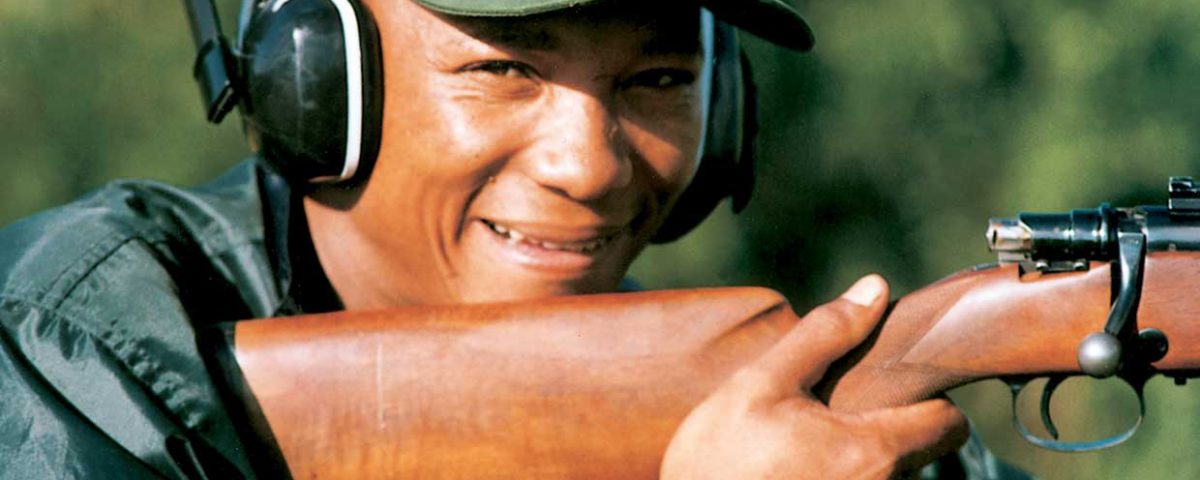

Is it not time to reconnect with our prehistoric hunting lineage and sharpen our hunting skills in a pristine setting such as offered in Namibia rather than being swayed by equipment-driven considerations? A hunter who practises shooting under field conditions and relearns the signs of the wild will be successful.

The hydrostatic shock theory remains controversial in some quarters, as very few African animals seem to drop to body shots with Magnums in the way propagated. The overall mindset amongst the hunting fraternity was nevertheless swayed towards the ‘high-speed’ model by accentuating amongst others that the flatter trajectory achieved by these cartridges translated effectively into longer shooting distances. This saw the advent of rounds such as the 264 Winchester Magnum, 7 mm Remington Magnum and 300 Winchester Magnum. In German-speaking countries this led to the rise of the 7×64 at the expense of the 7×57. The ‘faster-is-better’ concept also elevated the 8x68S as the calibre of choice and forced old stalwarts such as the 8x57JS, 8x60S and 8x64S with less impressive paper ballistic into undeserved retirement. The 8 mmm Remington Magnum pushed the performance envelope even further.

The ‘high-velocity’ advocates embraced even bigger overbore capacity cartridges of which Layne Simpson’s 7mm Shooting Times Westener (a necked down 8mm Remington Magnum) is a good example. Finnish manufacturers SAKO and Lapua jointly with British Accuracy International created the 338 Lapua Magnum which emerged in 1988 primarily as a long range military cartridge. Aubrey White in 1989 kept the ball rolling with the Imperial Magnum hunting series that utilized the full length .404 Jeffery case in various necked down caliber versions. Remington introduced some modification of these designs in 1999 as their Remington Ultra Magnums and sparked the design of super accurate “bean field rifles” destined to shoot deer on the far side of a Texan bean field at ranges exceeding 600 yards. Companies such as A-Square, Dakota, Weatherby, Lazzeroni and Sabi Arms of South Africa with their 338 Voschol (a necked down 500 Jeffery) are also considered exponents of the concept.

Telescope manufacturers played their role in supplying high-magnification optic instruments with up to sixty times magnification, some with integrated laser-range finders to fire the hard recoiling, barrel-eroding brutes accurately on these extreme ranges and beyond.

Not to be outdone, in 2000 Winchester introduced the John Lazzeroni-inspired short Magnum concept, followed by Remington and Ruger. The shortened 404 Jeffery case was used, claiming that the lack of the Magnum belt enhanced feeding and superior head spacing. Combined with the shorter, wider powder column, claims were laid of improved accuracy over the old established Magnum designs. The fact that a shortened action provides a lighter package with the same performance as the older Magnum designs is one of the frequently underlined virtues articulated by the marketers of this concept. Later developments such as the 375 Ruger in 2007 and various Blaser designs darted 2009 remained within this argumentative frame of more power from short and standard length actions using beltless cases.

“Where does the development in the hunting-arms industry leave the new or upcoming sport hunter of today? Does it mean that all hunters should follow the present model by embracing and endorsing the doctrine that dominated hunting for over six decades?”

Creation such as the 376 Steyr, 338 Federal, 45 Blaser and 8.5×63 Reeb steered away from the high velocity hype but have not taken the market by storm.

Where does the development in the hunting-arms industry leave the new or upcoming sport hunter of today? Does this mean when buying a rifle, modern ‘high-velocity’ offerings are the best or only calibers to consider?

In 1942 José Ortega y Gasset, Spanish philosopher and politician (1883–1955) shared some insights on the general topic in Meditations on Hunting, which admittedly represents a different era and time line. Yet he addressed fundamental matters worth considering.

Gasset already anticipated a skewed development in hunting with focus more on legislation or other industry-related considerations at the cost of skill expansion. He argues:

Adult reason directs itself to tasks other than hunting. When it does bother with the hunt, it pays most attention to preliminary or peripheral questions. It will seriously endeavour to improve the species by scientific means, to select the breeds of dogs, to dictate good laws for the hunt, to organise the game preserves, and even to produce weapons that (within very narrow limits) will be more accurate and effective. But one idea presided over all this: that the inequality between hunter and hunted should not be allowed to become excessive…

By implication this means that man will increasingly become more seperated from nature with hunting abilities progressively deteriorating. The basic characteristics of the hunt remain the same though and are not different from those of centuries ago, with the exception that the modern hunter’s success is possible due to equipment rather than basic hunting skills. Gasset’s premise suggests that fair-chase principles endure. This remains and important consideration when debating caliber choice. Should the practice of shooting game at long distances still be regarded as ‘hunting’ or rather shooting at live targets.

Maybe we should remember that our prehistoric hunting lineage legitimates hunting. Sharpening our hunting skills rather than preoccupation with trajectory, speed and other equipment based considerations will reconnect us with the basic instincts that define the hunter. Surely, hunters who practices skills under field conditions will bae able to shoot straight without need to rely on velocity and an array of optic equipment or devices to hunt successfully. The wider dimension of hunting should not be lost as aptly expressed by Gasset:

One does not hunt in order to kill; on the contrary, one kills in order to have hunted… If one were to present the sportsman with the death of the animal as a gift, he would refuse it. What he is after is having to win it, to conquer the surly brute through his own effort and skill with all the extras that this carries with it: the immersion in the countryside, the healthfulness of the exercise, the distraction from his job.

Namibia offers excellent opportunity to soak up the entire experience which includes the diverse scenery of the silent places often only touched by the change of seasons. The choice of calibre always remains personal but should not be based on paper ballistics alone. The old cartridges of yore provide all the penetration and performance required in modern times if fair-chase principles are applied. Companionship and a well-made rifle that shoots straight will further accentuate the reward of experiencing the great outdoors under an African sunset. Considering sustainability of the hunted species will still provide encounters worthy to be shared around the camp fire even if a true effort to hunt didn’t result in a kill.

This article was first published in the HUNTiNAMIBIA 2014 issue.