Eland Hunt at Saamgewaagd

January 14, 2019

A Tale of Two Kudu

January 14, 2019

A moment ago I saw the white shimmer of his body flicker through the leaves of a raisin bush about fifty metres ahead of me. I went down on my knees and slowly and carefully shifted to the side, keeping the bush between him and me. I then went down on my elbows and with the bow held up horizontally in front of me managed to reach a bush about thirty metres from the buck. I stood up slowly, drew the bowstring and let go. Taken by surprise, the big Ram spun around, stood for a few moments, uncertain, on his legs and then collapsed gracefully, first on his knees, then with his back legs following buckled. Slowly the pronk on his back stood up, fanned out and was caught in the rays of the setting sun. When I walked up to the downed animal it was still breathing, but the last slow breaths soon faded away completely. The pronk stayed open for a few more minutes, then it slowly collapsed and receded into the folds of tawny skin.

Witnessing the process of dying is loaded with powerful emotions: the onlooker is overcome with awe and incomprehension. The hunter-gatherers of the ancient land, now called Namibia, knew this through experience. They were especially aware of their own vulnerability in harsh and dangerous terrain, inhabited by elephants, lions, leopards, poisonous snakes and hostile human adversaries. The people who managed to stay alive in such circumstances viewed themselves as being favoured, looked upon with benevolence by the spirits, and as beings that inhabited the terrain of the outer-life and after-life. These people, the Ju’/hoansi, Nharo, Heikum, !Xu, Gwi and other “real people”, as they called themselves in contrast to the cattle herding or agricultural nations on the outskirts of the desert, lived their life in a close community, strongly dependent on each other in order to survive. The women gathered food, the men built up their strength and energy, listening to signs in the universe: stars, wind and weather, consulting special “hunting oracle disks” until they felt confident enough to go out in search of prey. Meat was for eating, and all animals had the same intrinsic value as food. Whether a few ostrich chicks or a giraffe, the size of the animal did not matter, as long as it could feed the community as well as possible for as long as possible.

Depending on the nourishment provided by meat, these people knew that their own survival depended on the death of another. But the realisation soon dawned that the dead animal was not only “meat”, but that surrendering its life to man expressed something of much higher value. Only someone close to the point of collapsing from hunger understands the sense of revitalisation that eating meat can bring: the feeling of fullness, of steady recovery, almost of rebirth. The burning hunger disappears, normal senses return, limbs slowly regain their purpose and their strength, the head starts thinking clearly again, emotions of hope, vitality, gratitude flood the mind.

In life-or-death situations like these, strongly-held beliefs accumulated in the individual, reinforced by the community, and supported by the experience of many generations, people remembered and forgotten, the ones that were there long before the ones currently alive – those who were fortunately given essence in stories and myths.

Any visitor to Namibia should take time to view some of the “holy sites” of our hunters’ past.

A photograph or trophy is a token of respect to the animal, just as much as it is a token of success and remembered experience to the hunter.

One prime exponent of this perception was that animals and people were seen as creatures of equal value, not the one more important than the other. There was a shared life-stream connecting all creatures in a common matrix of existence. Respect for the prey animal, in the deepest sense of the word, was inculcated in the hunter and the eater. There was a clear connection between living and dying. These elements of existence were interdependent, one directly affects the other, two poles of the same thing.

In today’s Namibia, we still encounter the evidence of this deeply spiritual relationship between hunter and animal. A visit to one of the surviving communities of hunter-gatherers in the far east of the Otjizondjupa Region or the deep forests of the Okavango or Zambezi regions still reveals traces and remnants of this magical way of living, although the ravages of civilisation have taken their toll in many of these communities.

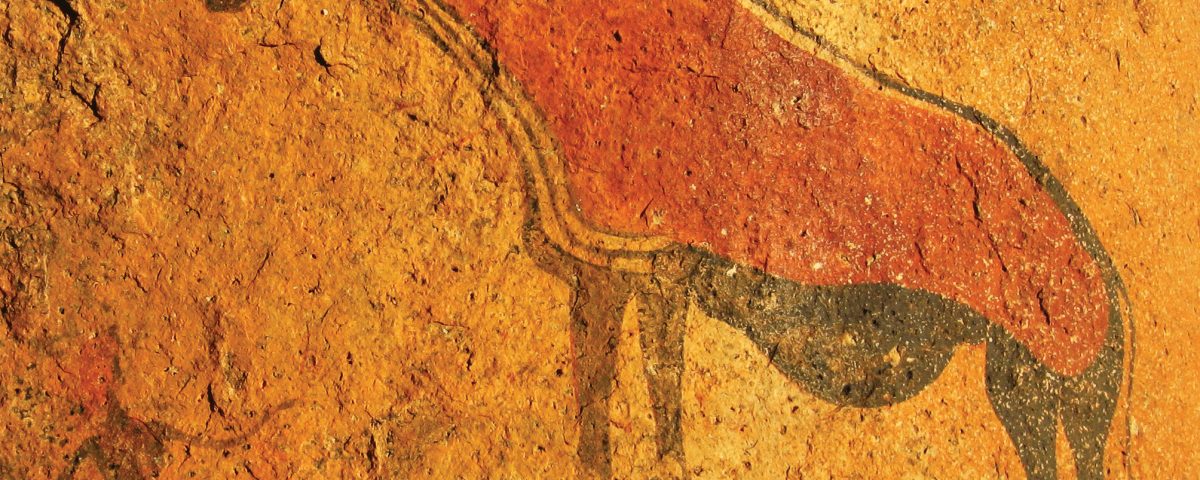

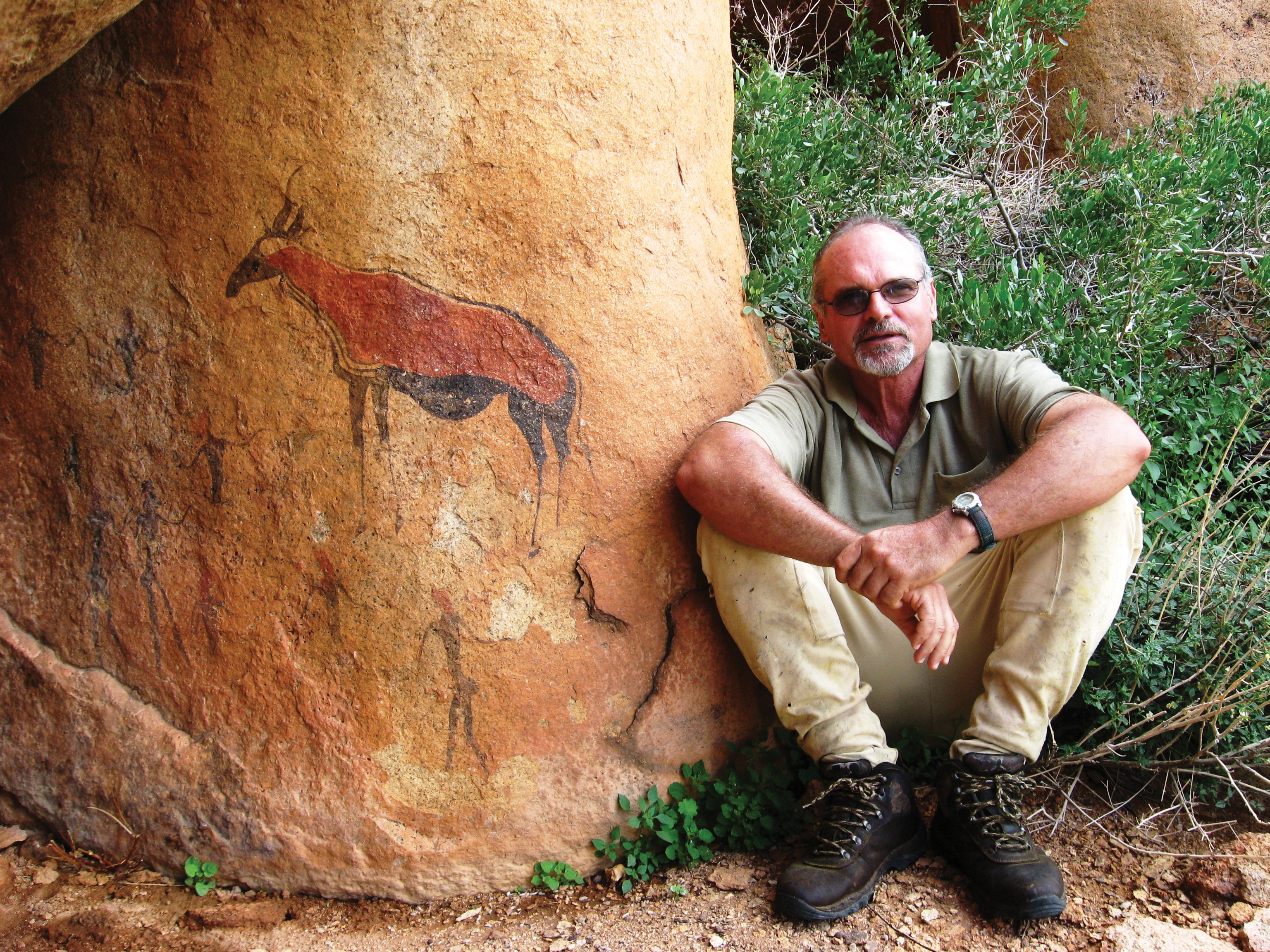

Nowhere is the perception of a supernatural bond between man and animal better expressed than in our rock art. Nobody can remain unaffected by the deeply spiritual symbolism of these paintings, animals and people intermingling on the rock face, the animals in most cases drawn with much more artistic intensity and reverence than the surrounding human beings. Any visitor to Namibia should take time to view some of these “holy sites” of our hunters’ past. A visit to Namibia is not complete without viewing some of our country’s rock art sites. Many of these sites are hidden away from the general tourist traffic and need a special effort, and often a substantial amount of physical fitness to reach and observe.

Remnants of this hunters’ magic still linger in the make-up of the modern hunter. This is made clear by the various “rituals” also practised by modern-day hunters. Visitors from Europe, for example, put a green sapling in the mouth of the downed animal, others smear the forehead and face of the hunter with dabs of blood, while others have to eat a piece of raw liver as a ritual act of gratitude for the success of the hunt. Felicitations of “Good hunting!” “Waidmannsheil!” or “Voorspoed, Boet!” even today accompany the hunter on his quest.

Photographs and trophies, to my mind, play the same role. A photograph or trophy is a token of respect to the animal, just as much as it is a token of success and remembered experience to the hunter. When the animal dies, the hunter is particularly aware of himself being alive. The animal dies for him.

Respect for the animal is still of prime importance when photographs and trophies are taken. Unacceptable practices, such as the hunter standing in a posture of arrogance with a cigarette in his mouth, one foot on the animal, or sitting defiantly astride the dead animal, and other “macho” practices of the 50s in the style of the “great white hunter” glorified by Robert Ruark or Ernest Hemingway, are fortunately a thing of the past. The recent debates on social media regarding trophy pictures of dead animals are therefore to be welcomed, even only to again inculcate a sense of respect and humility with regard to the animal that was killed.

Although we are no longer dependent on animals for sustenance, we, as hunters, still have the same duty to respect and have reverence for the animals we kill; the same gratitude, reverence and respect that our forebears from “primitive” society had for the animals they killed when they were hunting for food.

This article was first published in HuntiNamibia 2018.