The landscape appears completely lifeless. Hardly ever is the voice of a bird to be heard. In the ravines here and there stand leafless Moringa trees with their bulky, water storing trunks and just asleafless Commiphora glaucescens trees, their golden-brown trunks inconspicuously fitting in with the pale-brown landscape now gilded by the evening light. In this way, stopping every now and then to glass the surroundings, we return parallel to the course of the Chausib River and, as dusk falls, descend towards camp over the rocky ribs.

In this way the days pass; in looking over an awe-inspiring lonely landscape. At sunrise the croaking duet of the Rüpell’s Korhaans. In grandiose panoramas and the sight of Hartmann zebras moving on their paths over the ridges in timeless ease. And here and there a small group of springbuck. Then again only lifeless, windswept desert-plains and scattered gemsbok tracks on the game paths. This is the recipe for survival of the desert animals; continuously migrating from nowhere to somewhere in search of sparse water and fodder resources.

On a morning, we sit on the rocks of a little mountain, looking down onto the limestone ridges and try to look into the deeply cut incisions. We see Hartmann zebras move over the windswept ridges and a small group of springbuck, glassing in vain for a gemsbok. There, an old kudu bull dissolves from the ribs of rock at the foot of the mountain we sit on and steps onto a small quartz-gravel plain sprinkled into the broken terrain towards a Shepherd’s tree. It stops there to browse around the tree for minutes on end. Laying the marvellous horns – the tip of the left horn is somewhat broken – far into his back, he browses up into the little tree. The white lips in his coal-black face with the white chevron marking on the bridge of his nose pick every reachable leave full of devotion. Then he turns and steps majestically over the gravel plain, back into the ribs of rock, grey and ponderous. The kudu bull, pendant of the keen-eyed, restless gemsbok amidst the two great indigenous Namibian game animals, in their uniqueness en par with Africa’s other three great antelopes found elsewhere; the sable antelope of the Miombo Woodland Zone, the Lord Derby eland of the north-western savannas and the bongo of the gloomy equatorial rainforests.

When our hunt slowly draws towards its end, without us being able to find a gemsbok in the drought-stricken landscape, I decide to climb into the eastern, if one so likes the right, brain side of Ilala. This is somewhat more arduous, because on this side one first has to climb over a mighty Khomas Highland fold which runs north-westwards parallel to the Chausib. Therefore, we take the hunting assistant Erastus with us, who carries additional water. Following a zebra-path through the riverbed, which first leads over a limestone ridge into an isolated basin of quartz gravel, to then steeply lead up to the saddle of the Khomas Highland fold. In the basin, next to the zebra-path in the scanty shade of a scraggy tree, lie the bones and the horns, turned yellow, of an obviously ancient gemsbok bull, who, in the harsh, silent seclusion of this place, lay down to die and breathed the last of his tough, nomadic life. We look at the remains in silence for a moment, then we climb, still in the cool shade of the slope, towards the crest, in the saddle of which the crags and pinnacles of the rocky ribs stand out against the hot white light of the sun just rising behind it. Amidst all the lifeless rigour of rock and stone, there is the silhouette of a bizarre Commiphora tree, its branches becoming ever more refined to form a delicate filigree of outer twigs.

Reaching the saddle out of breath and soaked with perspiration, we now have the glaring light of day in our eyes, which certainly will turn hot. We sit down amidst the rocks and begin to glass the terrain beneath us. Soon we spot a few gemsbok. We climb down and start to creep up to the animals slowly moving away to the north. At midday the game eventually comes to rest on a small flat plateau at the foot of a pebble-strewn slope with a big, spreading Shepherd’s tree in the middle. From several sides, more gemsbok come moving to this spot and soon 15 of the big antelopes have gathered here, while we try to close in laboriously in crab-fashion over the rubble. At the edge of the group there is an old bull, always staying close to a cow seemingly in heat. When we have closed in to 200m, the risk that one of the many animals will detect us becomes just too great and we decide to risk the shot. But in an attempt to adjust for the distance, which is somewhat far for the heavy bullet, in “taking full bead”, Thomas fires above the bull. We are left to gaze after the antelopes, running off in panic in a big cloud of dust.

The next morning finds us on the saddle again. After a short while of glassing, we again detect gemsbok down in the plain and notice in delight that it is the old bull and the rutting cow. The bull drives the cow over a ridge into a deep ravine. Here we close in carefully and eventually realise that both animals are bedded down in an idyllic little valley. We creep up to the edge and are within convenient shooting distance now. The bull must just stand up then success should be certain. But suddenly the cow, all the time scanning into all directions, detects us. She stands up, looks up towards us for a short while and runs off. The bull is up and away with her without even pausing for a second. They stop after a while but now it is over 200m once more and the hurried shot misses its target. We all know the deep frustration of such moments. Thomas utters a few swear-words and declares: “Enough now!”

But one does not throw in the towel so soon and, once the first rage has ebbed off, we walk in the direction of the Kuiseb in a wide semicircle. Eventually we sit down on a ridge and start to glass again. We just see three gemsbok, which seemingly got our wind, make off over a ridge far in the south. It is hot noon now and thus makes little sense to go after them. First of all, we try to find some shade, which is not easy. At last, we lie down tightly pressed against a little stony ridge which offers the scantest shade from the hot desert sun, drink a lot of water and chew some biltong.

As it becomes cooler in the afternoon we rise from this hard resting place, beat the dust from our clothes and eventually walk into the direction where we saw the three gemsbok disappear. Carefully stalking along on the ridge, we suddenly detect the animals bedded down in a depression, sink to the ground and retreat into cover. Then we outflank the place and close in again from behind a rocky outcrop behind which the animals are resting, chewing the cud. In this way we come into convenient shooting distance. In the meantime, the animals have risen and start to feed, amongst them a bull. It is not the old fellow that got away twice, but we cannot be choosy any longer. As Thomas goes into firing position, I can see from his pale, tense features that a heavy burden now rests on his shoulders.

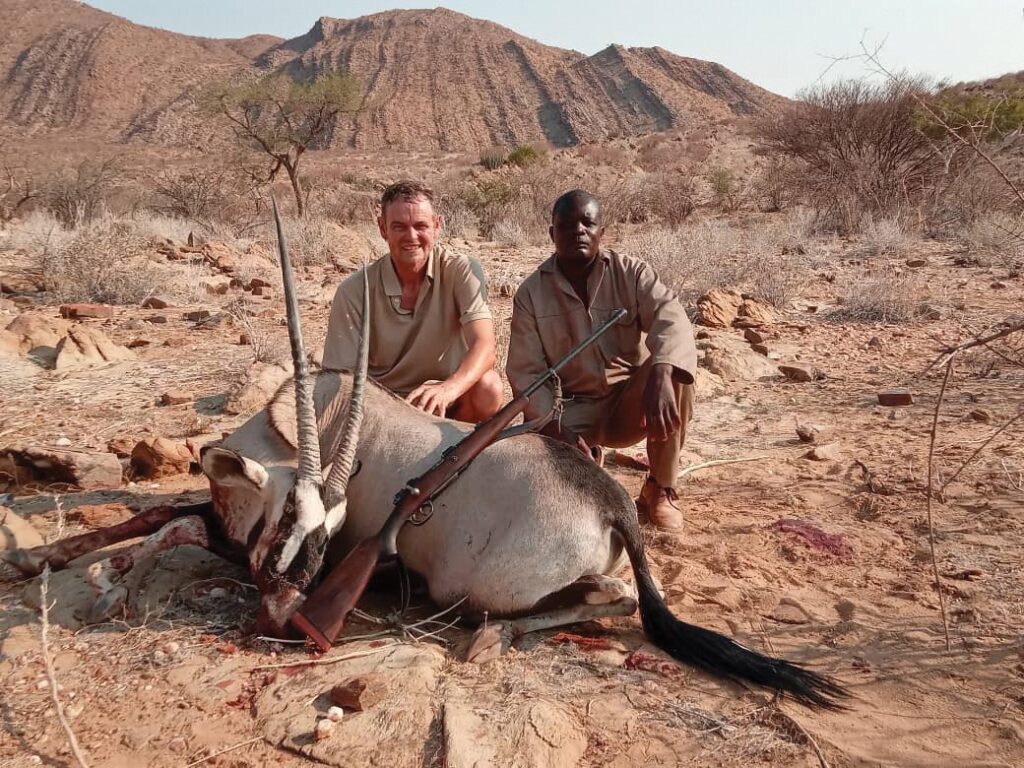

But the gemsbok bull, struck by the heavy projectile, collapses in the foreparts, gets up once more, but finally is down after a short rush. I nod to Thomas – few words are needed between us – then Erastus, who at first had remained behind, arrives and we go down in big relief. By now it is too late to retrieve the meat. Thomas and Erastus will have to spend the night next to our booty, guard the meat against the hyenas, which are plentiful in the Kuiseb River, and start to cut up the animal. We still have enough water, and they can prepare the liver of the bull on the coals. I give short instructions, then quickly look around in the vicinity for a place that I can reach in the morning with the car to load the meat. When I come back, Thomas squats behind the gemsbok bull, holding the legs, while Erastus is busy gralloching. I have the impression that Thomas is still in a turmoil of emotions; of huge, humble vacillation and the simultaneous awareness, that after all, this had been a great hunt. I give him a little slap on the slouch-hat under which he seems to squat down and a somewhat firmer slap on his back, then I set out on my way back to camp.