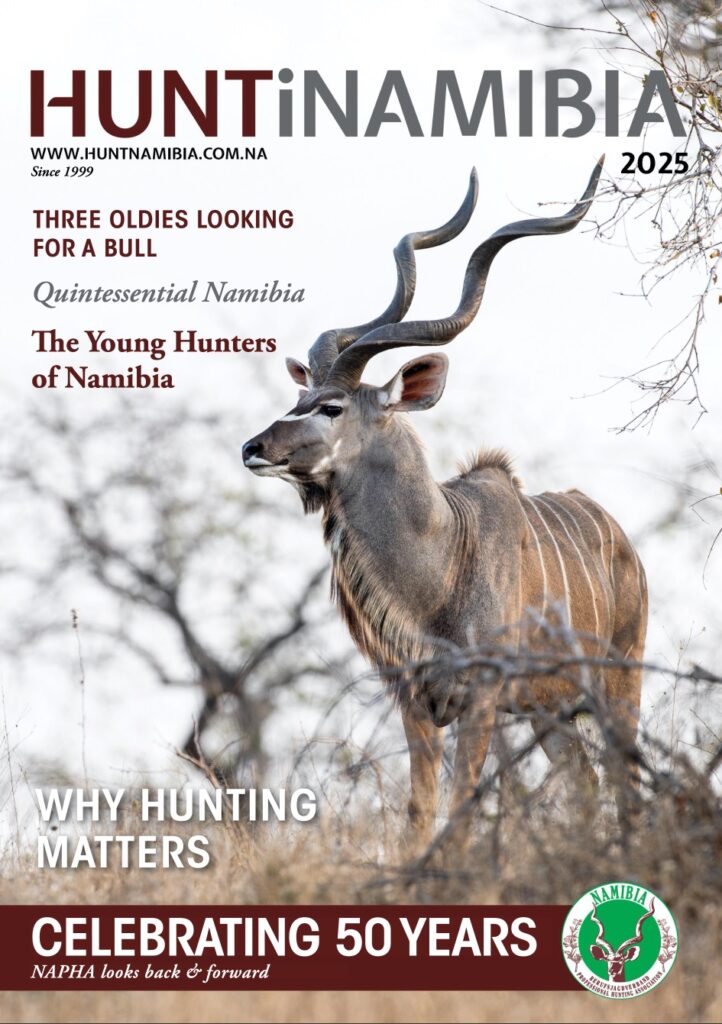

Itreasure hunting kudu. I appreciate the ritual of the hunt that joins hunter and hunted together with the land that is the mother of both man and beast.

And so it is not often that I find myself in the position where I hate the very first step towards such an anticipation. As we often find ourselves in uncertain situations, it was my turn, and I knew and believed from the get-go that this hunt wasn’t the one I wanted to comply with.

We had a filming team from Sweden with a list of the animals that they wanted to film for a series in Europe. One of these animals was, of course, the greater kudu, and I anticipated and voiced more than once that we would need a good ten days for a true portrayal of a kudu hunt. They all nodded in strong agreement, with the understanding that, seeing that they only had four days, we would make do with any possible opportunity that might arise, and hope and pray that we might stumble onto one of these magnificent beasts, while remembering to press the record button.

And so we started, my mind eased and ready and eager to walk into the beautifully unknown, ready to showcase Namibia in its fullest form, without any pressure, and without any predisposition. I was happy.

We hunted hard for two days before we had to move over to our next reserve. We were successful and harvested more than what we expected. But as time approached where we were to leave, whispers did not elude my ears: a sense of agitation and impatience that crept forward and over my shoulders which just didn’t relent – like a blackthorn bush holding on to me, keeping me back, and making me bleed.

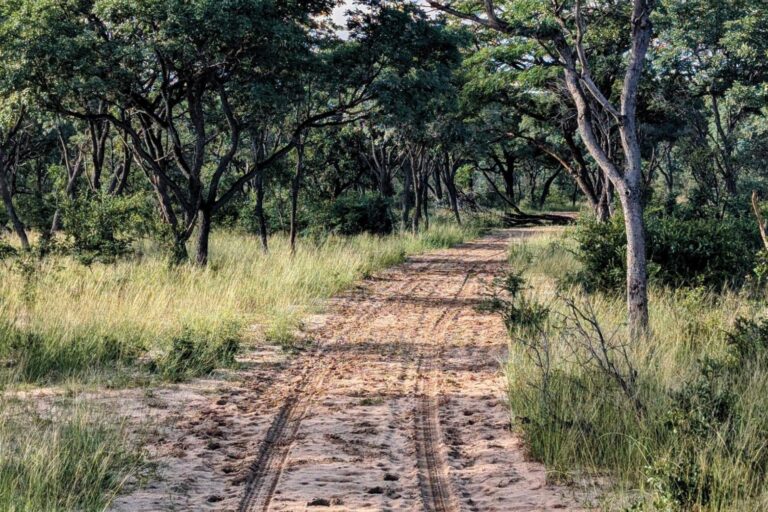

With this sense of disappointment stinging in my ears we got into the prepared vehicles and embarked on our trip to our next destination – a different habitat, a different part of Namibia, a different hunt. I trusted that the wind in our hair, music on the radio and the kilometres passing by would heal some wounds, but it turned out that it only evoked more of a longing to go back. We disembarked in the magnificent Kalahari, where savannah grasslands and witgat abound. But for them it just wasn’t enough. The ghost haunted and the ghost hungered.

After dinner the argument was finally made: “We want a kudu – we need a kudu to feature on this hunt.” And it was here, in this moment of futile disparateness that I developed a hatred of a kind that I hope I never discern in myself ever again. My face, as always, betrayed every emotion in its most illustrious degree, and I merely walked away, knowing very well that no matter the look on my face, or the image of my back, would ever change the mind of these self-righteous, entitled, wanting, undeserving and unworthy lot.

And so the next morning we set off, back to the land of the kudu, with a smiling crew, and a disgruntled PH.

The ridges on the mountains were slowly starting to glisten subtly and smoothly in the shy and slow dawn, a welcome reprieve to the two hours of silent, cold driving. My trackers on the back equally so, whether from the cold on the back of the truck or the absence of laughter from my heart. They, more than anyone, knew that no matter the outcome – the very cold would persist.

The truck was stopped at the foot of a hill, and while the hunter slowly gathered himself with binoculars, rifle checks and ammunition, I checked the wind over and over again, willing it all the while that it would dance fiercely, wildly, playfully and turning constantly as it would in the fiercest majestic thunder. But to no avail… the frost was crisp underneath my boots, the mountain spoke of protection and solitude, and I could almost smell the anticipation of the ghost.

Step by fateful step we climbed higher and higher, hour after hour, ducking underneath sekelhaak and blackthorn, and as the sun started beating down on us hard footfalls were behind me, and with a swear word every so often as I could hear shirts and trousers getting ripped apart, I felt that revenge was close. I wanted to walk them to the end of the world. I wanted them to feel and breathe and sweat ten very long, hard days. The way it was meant to be. At one point my tracker offered water, and in the moment where the hunter realised the reprieve, I turned around, whistled and adamantly showed that we had no time for a break. Onward, forward, no stop! I was going to the end of the world, demanding the sun to set, for the kudu to walk away, to survive, to be fitter, fiercer… and to be free.

“Make a plan.” All of a sudden this went through my head over and over again, as I had often been told by my parents. “And if that doesn’t work, make another one and if that doesn’t work, you are probably the problem.”