Message from the Minister – 2022

May 18, 2022

NAPHA and the age-related trophy measuring system: Preserving Namibia’s wildlife

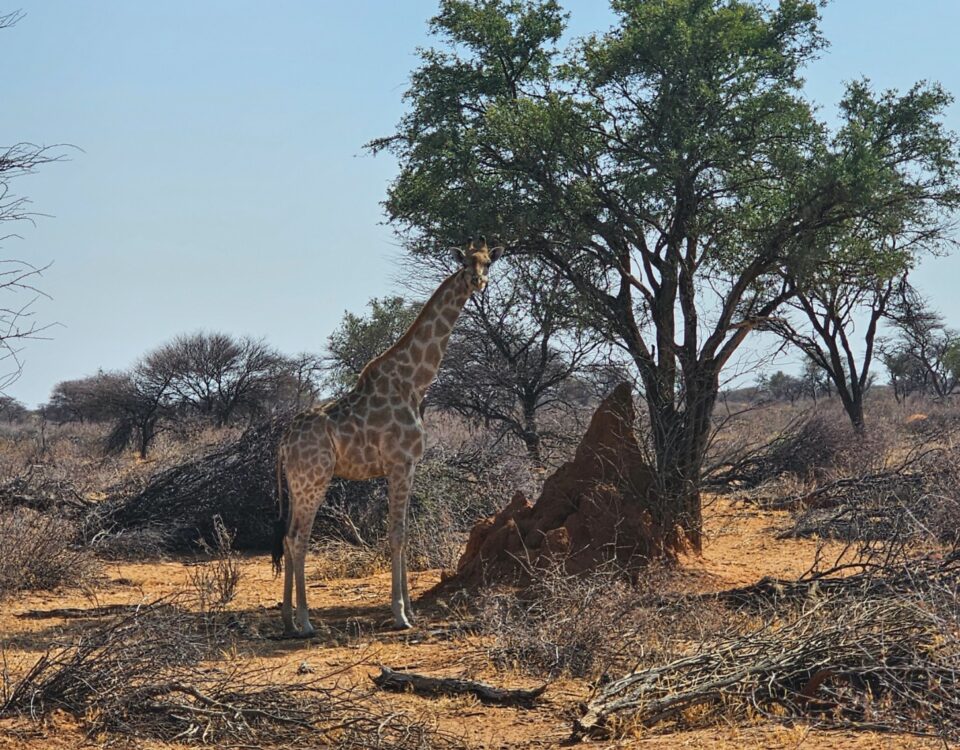

December 5, 2023Basically the debate is about how we are supposed to protect our wildlife from destruction in the face of the relentless encroachment of mankind. And that is where the first problem comes in – all of those screaming to protect our WILDLIFE actually mean certain animals – the big ones and the furry ones. They have the flagship species in mind: Elephant, rhino, lion, leopard, gorilla, giraffe, and zebra – the animals commonly associated with the general picture of “Africa”. Very few people are concerned about the bontebok or the grey rhebok, or even know what they are. No-one really cares to mention the small, the ugly and the less cuddly ones which just as much form part of wildlife. They are catalysts in the natural chain of ecology and biodiversity, which also includes the various plants. This biodiversity is needed to support all animal species, not only those few that everyone wants to protect.

Closely linked to this is the question of balance of the ecosystem. Where land is utilised, carrying capacity plays a significant role in the balance of nature. As we all know, too much of a thing is never a good thing. Too many antelopes, for example, will eat all the grass and none will be left in the dry season or for the other species. When antelopes starve, the predator populations will naturally thrive on the abundance of food, but too many predators will consume all the prey animals, and eventually die of starvation themselves – a total population crash, which is something to avoid.

Carrying capacity is the maximum number of units that can be maintained sustainably (i.e. balanced) in a given area utilising a natural resource within a given timeframe. Logically, it would make sense to try to maintain a population at or just below the carrying capacity.

That brings us to the question of “maintaining” population figures. We want wildlife populations to grow and be protected, but the human population continues to grow as well. As a result, wildlife habitats are shrinking at an alarming rate. In fact, Africa’s human population is growing so fast that the ever-increasing demand for land is the biggest item on all African government’s agendas. More land for human use will be to the detriment of wildlife – that is a given.

“Animals are safe in game reserves and national parks”, the armchair conservationists are screaming. Well, if it comes to that we have failed! Little islands of conservation areas would decrease potential genetic signature dispersal, and it would also lead to a concentration of prime poaching species.

Wildlife management is about maintenance of the land, water points and water systems, erosion control, anti-poaching, access-construction, fences, invader plant control and wildlife population control. It is what game rangers and park wardens, land owners, farmers, ecologists, pastoralists, conservancies and concession holders do all the time: Putting their knowledge about ecosystems, behavioural patterns, growth cycles of plants and animals, and interactions between all these, into an overall plan that is constantly adjusted to account for changing circumstances and needs in a given area.Larger areas need less direct management than smaller ones, as they tend to self-regulate to a degree.

Ideally, one would want an area to be large and left alone, but unfortunately such areas are getting less and smaller, thus more direct human input is required. Wildlife population management seems to be the hottest topic these days as it involves the removal of excess animals from an area.The cry from the armchair conservationists will be that if a population starts to naturally adjust to the carrying capacity, why manage it? The answer is that firstly the carrying capacity is constantly changing with the weather conditions. Secondly, management is needed to prevent human-wildlife conflict (HWC) and to prevent animals dying from starvation, over-predation, disease breakout and other factors that lead to drastic population declines. All these criteria would not be such a problem in large areas, but large areas actually do not exist anymore. The narrowing corridors and open (human-populated) land between the “wildlife islands” are the cause for HWC, one of the biggest concerns of our conservation era. People who live in areas bordering parks and game reserves have to deal with wild animals on a daily basis. This creates resentment, the exact opposite of what we are trying to achieve. Some communities want ALL elephants removed because they are tired of having their fields – an entire year’s food supply – destroyed overnight. These communities in remote parts of the country are ultimately responsible for the survival of wild animals and the preservation of the supporting habitat. They have to benefit from the wildlife otherwise we are losing.

Too many elephants in an area eventually destroy their habitat by over-utilisation. Such areas (usually along watercourses) are devoid of all intermediate trees and shrubs. Only larger (somewhat mangled) trees remain. The full extent of this becomes more visible from the air.

This is where population management comes in, the removal of animals from an overpopulated area to maintain carrying capacity. The methods are hunting (for meat or trophy), culling, or capture. All of them are regulated by the wildlife authorities through some type of permit system, based on the management plan for that area. By contrast, poaching is indiscriminate and benefits only the poacher.

Culling involves the removal of a certain number of animals irrespective of gender or age, so that the dynamic of the population is not skewed by human bias. The aim is to reduce the numbers as quickly as possible with minimal impact on the remainder of the population. It is usually done at night by a team of expert shooters and butchering teams. The advantages of culling are the rapid reduction of numbers in a very short period of time, and the meat is very hygienic as it is processed quickly. Also, the remaining population is usually unaware of this action.

Meat hunting mostly takes place during daylight, and is generally more biased as to which animal is harvested. The hunter will take one or two animals, of a specific gender or age group, for his own meat supply. The reduction impact is a lot slower than that of culling, but meat hunting can be implemented continuously over an entire season.

Trophy hunting attracts the most criticism by far. It is generally seen as a “blood sport” practised by the wealthy to collect animal heads. Yes, that may be the case, and it may be the reason why hunters travel to distant places (supporting local economies). Very few people, however, are aware of the conservation benefit of this method: the population impact is the lowest but it generates the biggest income. Yes, good money is made – by entire rural communities who provide the services for trophy hunting in remote areas. The economic factor is so remarkable that people are keen on creating more habitat for wild animals. Investors are prepared to buy land, usually marginal livestock land, and convert it back to a habitat suitable for game herds. This gives the local people a sense of ownership because they are actually helping the wildlife populations to flourish, with the incentive to be able to ‘harvest’ a select number per year. No one will over-harvest and deliberately destroy their source of income, and game populations in southern Africa have therefore increased drastically even though a controlled number of animals are hunted every year.

Game capture is a fast method for the live removal of animals. The most common way is to chase them with vehicles or helicopters into a funnel-shaped chute or into hanging nets and then load them onto a truck. This generally causes quite a bit of area disturbance, albeit short-lived. There are also various methods of passive capture, such as a trap at a water hole or salt lick.

People who do not [want to] understand the need to keep animal numbers in check will ask: “Can’t we move them to another place?” They usually mean the flagship species, mentioned above. The question is – move them where? Where should we move lions? Or elephants? To areas that already have them in excess anyway? This inevitably brings us back to the issue of ”available land”.

Let us look at elephants for a moment. Every available piece of land that can support a “viable” population of elephants has already got them [and too many]. Land that does not have elephants either cannot support them, cannot be protected sufficiently against poaching, or the human communities living in and around that area do not want them because they destroy crops. We are talking about thousands of elephants that some areas have too many of. Sub-Saharan Africa still has over 300,000 [and growing, naturally] elephants, but with nowhere for them to go. Should we put them into Central Park in New York? How long would it be before NY residents start complaining? Yet it is people like those living around Central Park, the city dwellers, the “good to do community”, who are quick to criticise the management of elephant numbers in Africa – but few come up with viable solutions.

Imagine putting 20 lions in Central Park… Who wants more lions? Definitely not the communities in rural Africa. Many of them kill the lions themselves, either by shooting or by poisoning (horrible), because their governments cannot solve the problems within acceptable timeframes. In fact, besides the private game reserves that already have the big cats for their tourists, the only people who actually want lions are those who live in cities or on another continent.

How do we create habitat for wildlife when available land is decreasing? By creating a value for these animals so that the people who live with them will benefit – in the form of financial compensation, jobs from hunting and photo tourism or the meat of hunted animals.

The crude way of putting this is: If it pays it stays.

You have probably heard many hunters, like myself, say that hunting is conservation and that sustainable utilisation (SU) is the only way forward. It is not, but right now it is the most advanced conservation model that we have for the protection of habitat in rural areas with marginal communities.

We utilise our [natural & mining] resources to exist, yet we criticise hunting, the one activity which is a management tool for a resource that is 100% renewable in an expedient time-frame, produces protein, income, jobs and the incentive to coexist. Without this coexistence, wildlife numbers will be decimated (poached) by the increasing human populations through their natural urge to live, and land will be cleared to make room for agriculture. It is this uncontrolled utilisation that will ensure the extinction of species. Sustainable utilisation, on the other hand, contributes to the well-being of local communities in exchange for them “being tolerant” of having to live with wild animals at their doorstep every day.