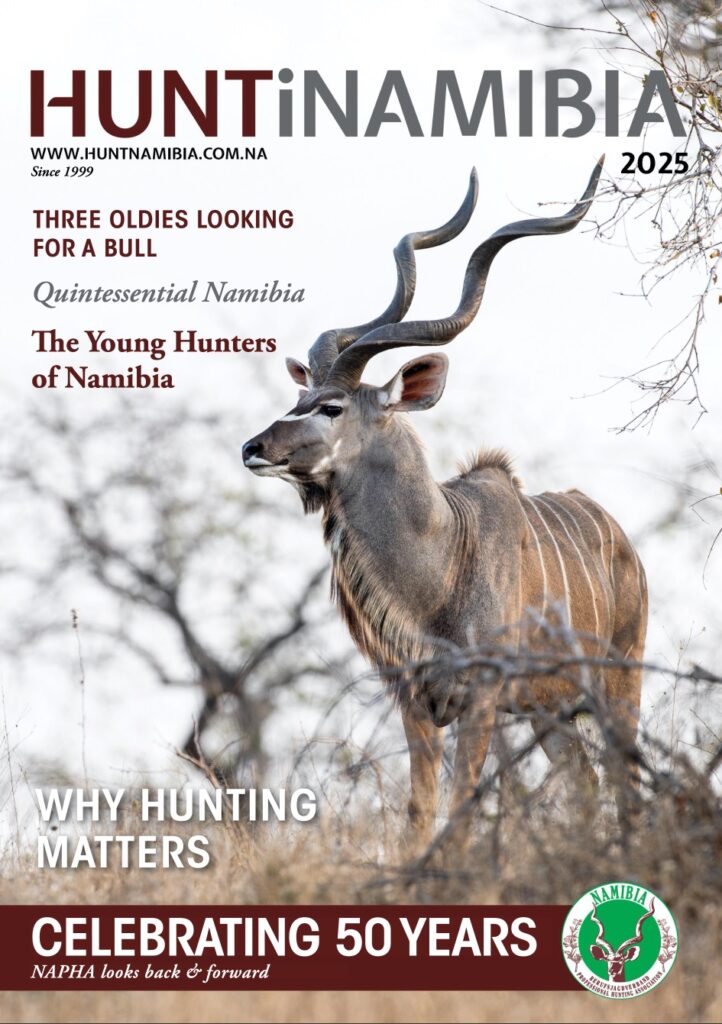

Securing the Future of Ethical Conservation Hunting in Namibia

Namibia’s hunting community stands at a pivotal juncture. For five decades, professional hunters, trackers, operators, conservancies and rural partners have protected wildlife and ensured that land remains dedicated to conservation. Our model, grounded in ethical hunting and sustainable use, is recognised worldwide as one of the most successful conservation systems.