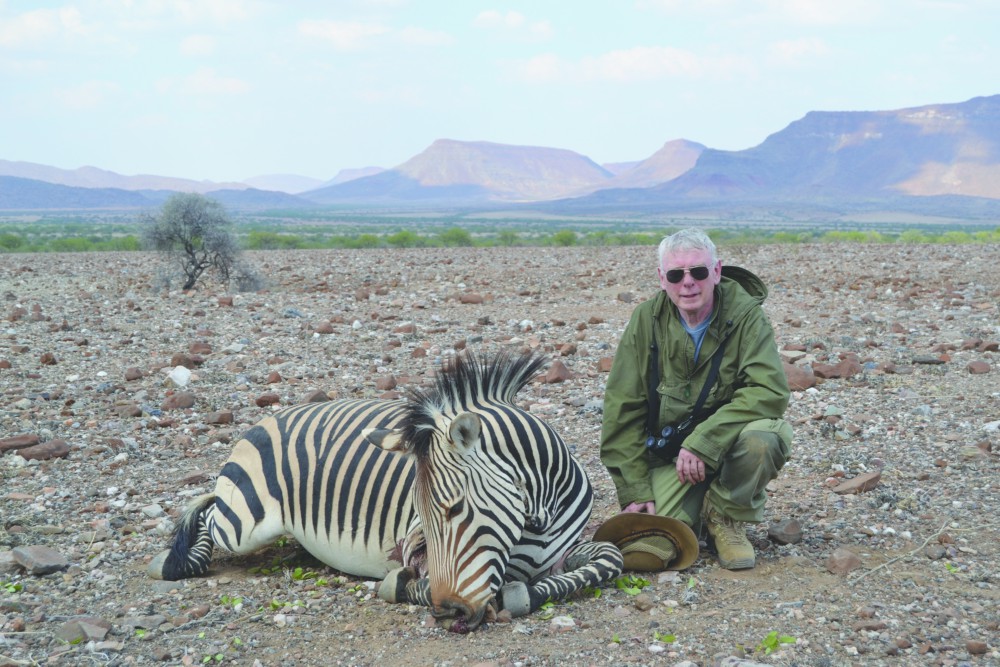

Good sport & fair chase – mountain zebra in the Namib

August 16, 2017

Caprivi dreaming

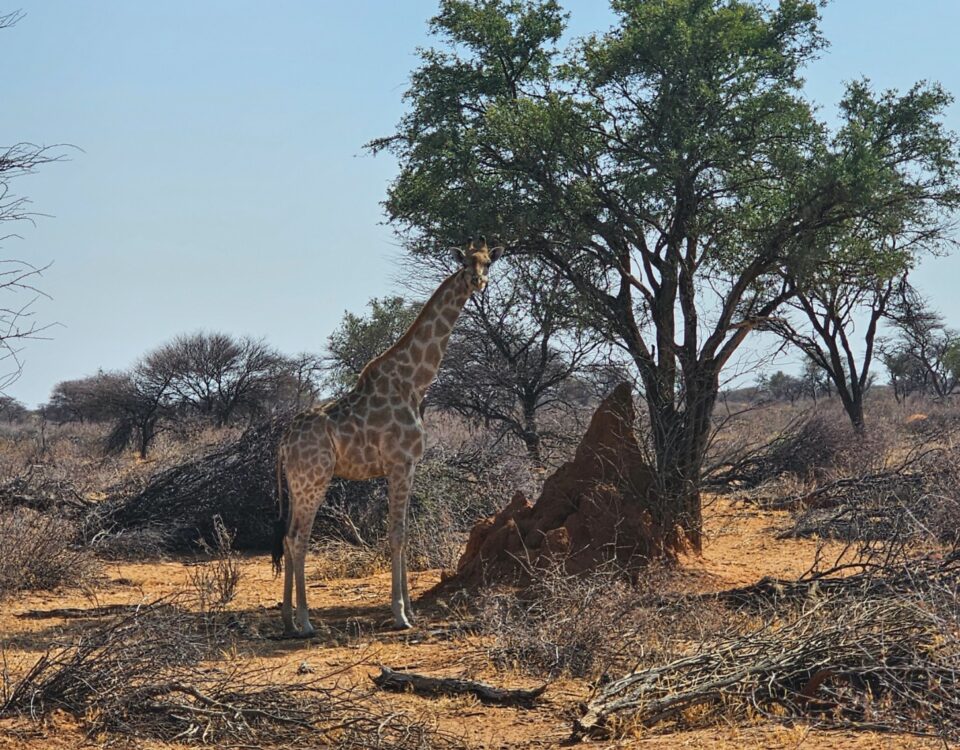

August 17, 2017H artmann’s mountain zebra, one of Namibia’s endemic species, remains one of the most sought-after trophies and exciting hunts that Namibia can offer. This is especially true in the far northwest of the country where they occur naturally and can still roam free, traversing mountain ranges and desert plains without the hindrance of fences.

Hunting Hartmann’s mountain zebra on foot in one of the communal conservancies of northwestern Namibia is demanding, a great challenge and truly exciting. This we experienced first hand while on a hunting trip in the Puros Conservancy.

Our adventure started at Wêreldsend, the IRDNC base camp 60 km east of Torra Bay, a well-known fishing spot on the Skeleton Coast. We left Wêreldsend on a chilly morning in early June for the six-hour drive to Puros. This drive is an adventure in itself. One travels through the most breathtaking landscape, which in the middle of the day looks harsh and unforgiving, but early morning or late afternoon that same landscape turns into the softest shades of pink, blue and purple.

After checking and shooting in the rifle we set off for a walk on the dry mountains northwest of Puros village, accompanied by the Puros conservancy field officer. We carefully searched the mountains and gullies for any sign of life. As it was our first day we were not in a hurry and after the long drive enjoyed being outside, with a strong, cold westerly wind in our faces. We enjoyed being out in the veld, stretching our legs after the long drive and becoming accustomed to the vastness of this seemingly endless landscape. The grass cover was sparse to non-existent and we only found a few gemsbok tracks leading down to the lush green Hoarusib River. In this harsh landscape the riverbed is a true oasis where animals find some greenery and water, but there also lurks the danger of two semi-permanent lionesses, always on the lookout for any sign of weakness!

Early the next morning we found ourselves in the Okongue area, southeast of Puros, on a vantage point high above the plains where the first rays of the rising sun painted the isolated bare rocks and grey lifeless soil with warm shades of gold. Patches of grass from previous exceptional rains were still in evidence, although few and far between. The conservancy has earmarked this area as an exclusive wildlife and hunting zone.

It was so cold that we struggled to steady our binoculars. We scanned the mountains and valleys, because the zebra move back into the mountains after their nightly parade down to the plains. Eventually we located a family group of seven zebra at the foot of some distant mountains. They seemed impossibly far away. “Here you can see to eternity,” my friend remarked dryly. There was no wind and we approached them carefully from the west. Gemsbok could be seen scattered over the plain as mere dots. Two ostriches kept us under surveillance from a distance and slowly started to move away from us. Crossing the ridge, the zebra were still 400 metres away – with no cover between them and us. We were also slightly above them. They were grazing and hadn’t noticed us yet. With gemsbok to our left and right there was little we could do, safe for getting comfortable and hoping that the zebra would move towards us. We identified two stallions, one older than the other. then, unfortunately, the wind picked up and started playing its usual games in the mountains.

The zebra immediately smelled us. First they started moving towards us, but recognized their mistake and to our utter dismay fled up the mountain and disappeared over the ridge. The friend jumped up and suggested to get going and cut them off. I knew it was useless because Hartmann zebra are the undisputed kings of the mountains. There is no blocking them, as I found out earlier in my career as an inexperienced hunter. Many a time I had to return to base totally frustrated, having tried to outsmart them. They seem to grow wings on their feet. I decided to keep quiet and let him experience the grace of these wonderful animals. We rushed up the mountain huffing and puffing. Arriving on the other side of the ridge he was amazed at the light-footedness of the zebra. They were already hundreds of metres away from us. I just chuckled softly and suggested we look for other game and come back the next day. By now the wind had picked up and there was no way we could catch up with them.

We left at five o’clock the following morning armed with thick jackets, rifles and binoculars. The strong easterly wind was bone-chilling as we made our way up a mountain west of the Okongue plains. When the sun rose over the horizon, dust clouds in the river below drew our attention to three zebra taking a dust bath. A stallion and two mares. Another family group was on its way from the valley into the mountains and disappeared from sight. The other three zebra seemed at ease and we sat quietly, just watching them for a while. A gemsbok appeared on our right and looked in our direction. Satisfied that no danger was looming he slowly moved away from us while feeding. Springbok stood quietly in the valley, trying to catch the first warmth of the early sunlight. We started our stalk down a gully, out of the zebras’ sight, and then upriver towards them. As we inched forward, using every little bit of cover and shadow for camouflage, we almost walked into a kudu bull. We waited for him to move on and then continued our stalk. By now the sun was shining with all its ferocity and it was hard to believe that it had been so cold earlier on. The wind also didn’t help to make the stalk easier and changed more often than my wife changes her clothes. In the meantime the zebra had decided to move out of the river and were now feeding half-way up the mountain.

Now we were sitting with a great dilemma: there was very little cover between us and the zebra, making a stalk virtually impossible, and they were higher up than we were. “Did we waste too much time on the stalk up to this point,” I was asking myself, contemplating various ways to get within shooting range of the zebra. Using milk-bush (Euphorbia damarana) for cover we crawled towards the zebra inch by inch – look, crawl, wait, look, crawl, wait – trying to be as quiet as possible on the loose stones and steep gradient. Wearing shorts, it felt as if the stones got a couple of degrees hotter with every inch. They also cut into bare flesh. When I turned to see how my friend was doing, I froze. A gemsbok was looking straight at us from no more than 30 metres. It had appeared from nowhere. “Stay very still,” I hissed. “What?” “Stay very still,” I hissed again, this time rolling my eyes towards the gemsbok, still watching us. Why do animals have this cunning ability of always catching you in the most awkward position when you cannot afford to move? After staring us down, satisfied that our limbs and back had endured enough pain, he trotted on. We waited for a while before we dared to look if the zebra were still there. We only saw two: the third one, our stallion, had left. I scanned the mountain, which by now sported all shades of grey and white in the blinding sun, making it extremely difficult to see zebra – believe it or not. My friend and I were lying next to a milk-bush, trying to use its limited shade for cover. There was no wind and Old Spikes had no sympathy for us. I was still scanning the area for the stallion when he suddenly appeared from behind a bush and joined the other two again. Whispering, I pointed to the position of the stallion. Wasting no time, we got into position to shoot. Although still 150 metres away, I felt comfortable that he could take the zebra. He inched into position at a snail’s pace, very aware that one miscalculated move could cost him this opportunity. I watched anxiously from the back, my attention alternating between him and the zebra. The stallion immediately raised his head and I could see his nostrils opening wide. Without taking the binoculars from my eyes I looked at the hunter and was relieved to see that he was in position and about to shoot. As the shot rang out I saw the bullet flying true and the stallion running downhill. After eighty metres he went down.

That night there were great festivities as zebra meat was delivered to the village and the fires got going at Puros.

As for my friend, apart from some cuts and bruises, a Namibian dream had come true – hunting the King of the Mountains, on foot, in its natural environment.

This article was first published in the HuntiNamibia 2017 issue.