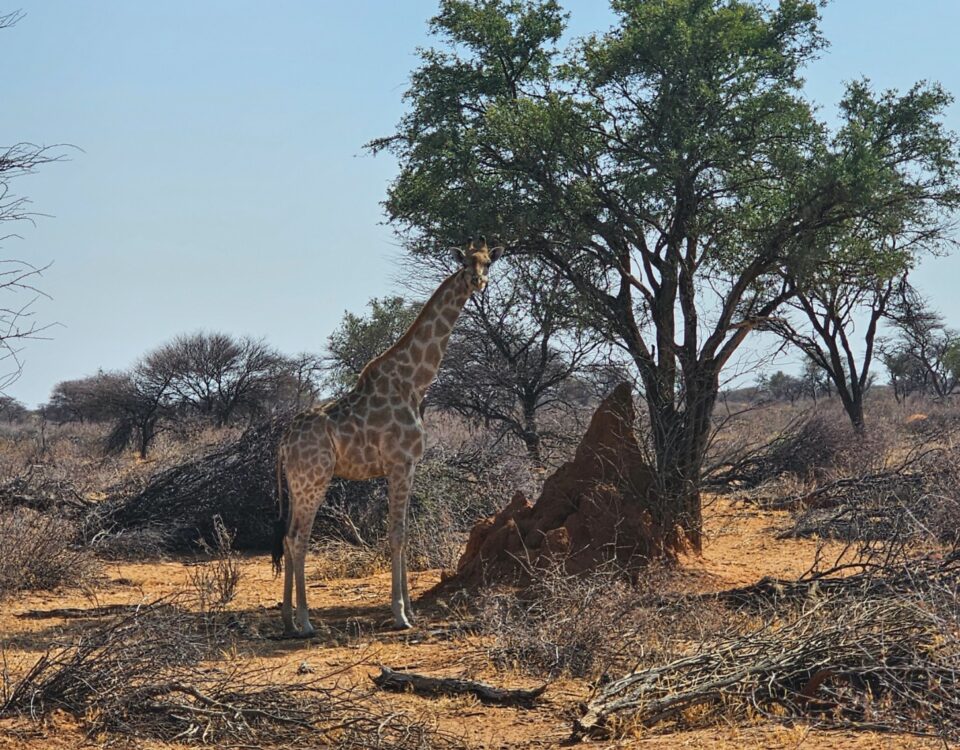

Main photo ©Bernd Wasiolka

The vegan hunter

April 20, 2016

Leo and an “own-use” elephant bull

April 20, 2016W hat makes the study of leopards south of Windhoek in the Auas Oanob Conservancy so interesting, is that farmers are taking the lead. They initiated the study and are collaborating with researchers and the Ministry of Environment and Tourism in their quest to gain scientific information on leopards sharing Namibian farmland. This information will be key to improving farm and herd management and ultimately reducing human-wildlife conflict. By fitting GPS collars to a number of leopards and analysing leopard movements over time, the project’s research activities and their management implications include the following:

Home range size

Studying home range size will provide a sound understanding of the average area single leopards cover and how long, on average, an individual leopard stays in a particular area. This information will help farmers to understand how leopards move through their land, and if problems with stock raiding do occur, they will be better able to identify the animal causing the problem.

Farmers can adopt their management strategies according to the findings and preferably use or avoid certain areas for grazing herds with younger calves.

Habitat preference

This part of the study will provide information on whether or not leopards prefer certain habitat types, how habitat is structured and how much time a leopard is spending in a particular habitat type. If leopards spend significantly more time in certain habitat types, farmers will not use this habitat type for grazing cattle herds with younger calves.

Feeding habits

Feeding habits and prey preferences are another critical factor in understanding the farmer-leopard conflict. The key question is: are leopards opportunistic hunters which randomly take livestock, or have certain individuals learnt to specialise in hunting livestock? If it turns out that certain leopards do specialise in hunting livestock, we could specifically target these problem animals to relocate them. They could be part of a well-organised trophy hunt that would generate some revenue for various stakeholders. Translocating cats from one area to another may not be the answer, however, because leopards are known to walk back over long distances to their original hunting ground. It may be better to hunt them where they are (see quote by Reinhard Friederich).

“Co-existence between humans and wildlife is not a romantic and ‘green’ notion; it is critical to our country’s economy. The tourism industry is vital to our country and Namibia’s wildlife. Big cats, like leopards, are one of our greatest attractions”, says Jörg Melzheimer, the leader of the project which is financially supported by the Go Green Fund.

Improving farm management, reducing losses and thereby promoting the coexistence of leopards on commercial farmland will be beneficial to the entire country. In Namibia the livelihood of many people depends on livestock farming. We need to reduce financial losses through better management of our livestock herds. Only then can co-existence of leopards and humans be ensured.

This article was first published in the 2015 Conservation & the Environment in Namibia magazine, a special edition to celebrate 14 years of Nedbank’s Go Green Fund.

Translocation not always the answer

Reinhardt Friedrich, author of the authoritative book Etosha: Hai//om Heartland, writes the following about the relocation of animals into the Park since the 1970s.

“The relocation activities can be considered successful, but this, unfortunately, cannot be said about those for cheetahs, leopards and wild dogs.

Of the 15 individual cheetahs that had been released at Ombika and Halali, some perished at the southern border, since the fence prevented them from returning to their hereditary hunting grounds in the south. One of these animals however managed to get through the fence and was later spotted in central Namibia. It was identified by means of an aluminium chip on its ear, with which all animals were marked prior to their release. Other cheetahs fell victim to lions, leopards or hyenas, since these predators were unknown to them from their previous roaming areas. It is not known how many cheetahs eventually survived.

The leopards that had also been released into the Park, all got away and found their way back to their original hunting areas.”