The presence of game rangers & hunters deters poachers

June 13, 2016

The core of hunting

June 13, 2016U

li and I share a special passion: old, big elephant bulls. When he was planning his second hunt in Bushmanland in eastern Namibia, he asked whether I would like to come along. In 2007 he had hunted an old elephant bull there with Kai-Uwe Denker, but the pachyderms were still beckoning. I agreed enthusiastically, and Felix Marnewecke, the professional hunter, had no objections.

At the 2012 Dortmund show we arranged the trip.

Our hunting area, the Nyae Nyae Conservancy in Bushmanland, enjoys an excellent reputation among experienced elephant hunters. For ten years, until 2011, Kai-Uwe Denker was in charge of hunting there. Among other excellent trophy elephants, he collected two 100-, two 90- and nine 80-pounders with his hunters. In 2012 Felix Marnewecke, with a second PH, took over the approximately 900 000-hectare concession area. In the east it borders on Botswana and in the north on the Khaudum National Park. The small settlement of Tsumkwe is situated in the centre. The number of elephants in the national park and neighbouring Bushmanland is estimated to be in the

2 500 to 3 000 bracket, with the likelihood of increasing. Six trophy and four non-trophy elephants on the quota demonstrate the retaining and sustainable approach.

The Nyae Nyae Conservancy is home to approximately 1 000 Ju/‘hoansi San people who have more or less settled there. The Bushmen, nowadays named politically correctly as the San, opted for cooperation with professional hunters, the nature conservation authorities and the WWF on usage of the area in terms of hunting and conservation. For their traditional hunting with poisoned arrows and traps, an additional quota was set aside for their use.

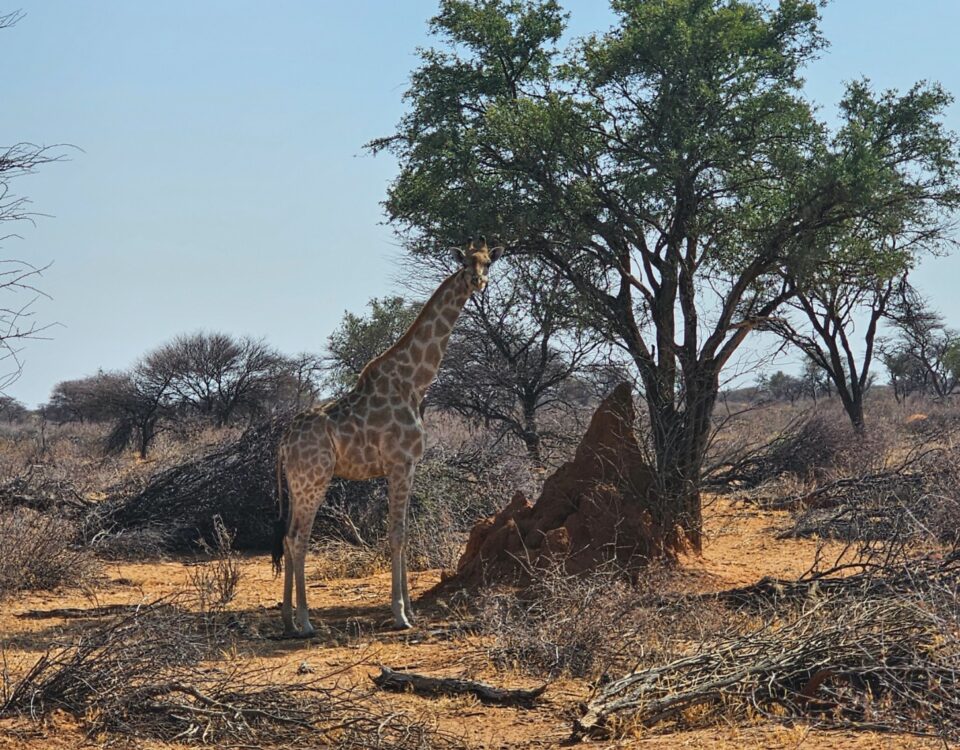

Plains-game species found here are eland, giraffe, roan, kudu, gemsbok, duiker, red hartebeest, blue wildebeest, springbok and steenbok. Predators are lion (these are scarce and there is no quota at present), leopard and spotted hyaena (both huntable game), and the protected African wild dog. This very arid region is characterised by sandy soils, tree-and-grass savannahs, thicket areas, and large saltpans. In good rainfall years, the saltpans are a paradise for water birds, especially flamingos. The biggest of these is Nyae Nyae Pan, which lent its name to the conservancy.

On the tracks, the classical way

Compared to many other hunting destinations in Africa, travelling to Namibia is easy, almost comfortable. Flights are on time, the immigration regulations are hassle free, and Namibia has a well-maintained infrastructure. From Windhoek it took us only seven hours to reach camp, which lies approximately 30 km south-east of Tsumkwe. We were chauffeured in a minibus by Theresa, the Owambo camp manager, and her husband. The camp is well situated under an old, giant baobab.

Like his predecessor Kai-Uwe, Felix conducts his hunts the classical way, following the tracks of the old tusker. This means walking 15 to 30 kilometres on most days. Our three experienced Bushman trackers, Dam, whom we called Robert, Kashe and Kxao, were going at a rather fast pace when the track was easy to follow. On two days we exceeded the 40-kilometre mark. But I must admit that to find tracks along the roads and at waterholes, we used the Toyota.

Our first hunting day

While looking for elephant tracks, we saw plenty of game: wildebeest, roan, kudu, ostrich and elephant cows with calves. At nine o‘clock we happened upon a huge track, and barely an hour later, we were close. It was a fine 70-pounder with a tusk-less companion. On most elephant hunts this is the exact moment a shot would have been fired, but Uli and Felix were out for bigger game.

“Like his predecessor Kai-Uwe, Felix conducts his hunts the classical way, following the tracks of the old tusker. This means walking 15 to 30 kilometres on most days. Our three experienced Bushman trackers, were going at a rather fast pace.”

In the afternoon we found the remains of a leopard kill. Vultures had led us there, but when we arrived, the meal was already finished. We resumed the search at two thirty that afternoon, following another track for two more hours, which led us to an old 50-pounder, creating the impression that elephant hunting here was easy. But you should always keep the walk back to the vehicle in mind! Back at the camp during sundowners we reflected on the 20-kilometre walk. “Good exercise, for a start,” was Felix’s only comment.

It can be bitingly cold between sunset and sunrise in the African winter. With night temperatures around freezing, getting up and washing your face in the morning takes willpower. But when temperatures reach the 30ºC mark during the midday hours, you long for a cool, refreshing drink.

The next days were filled with unforgettable experiences, not to mention seeing a great deal of game. Because of the low hunting pressure, elephants in Bushmanland are not as hard to track as in other areas where there is more hunting and poaching. Nevertheless, when the pachyderms caught our scent, they disappeared quickly and virtually noiselessly.

The wind changes quite often, especially around midday. The elephants also reacted strongly when we were not paying sufficient attention and making too much noise. But this made them run for ‘only’ five or six kilometres before calming down again. As records indicate in old books, during the days of commercial ivory hunting 100 years ago, these distances were much greater.

Early the next morning we found fresh tracks left by several bulls. Two hours later we saw them: four young bulls, one of them already carrying 65 pounds, and an old 70-pounder.

Own-use elephant

The fact that old elephant bulls do not necessarily carry big ivory was confirmed three days later. Again we took off in the morning, following the tracks of two old bulls ‘with huge feet’. We caught up with them around midday. They were clearly old, but the tusks were thin and short. I managed to take pictures from less than 20 metres, as if those old gentlemen knew that we only wanted to observe them. “The old, lesser bulls and those with short, broken-off tusks are reserved to be shot as ‘meat elephants’,” Felix explained.

This kind of hunt is as interesting as pursuing a big tusker, but the costs are similar to a buffalo hunt. The ivory cannot be exported, however. It is kept by the Namibian nature conservation authorities. We have more than enough of these old, lesser bulls. We could take a few more of them out without harming the population and rather save some of the young 60-pounders. “In the early evening on the way back to camp, besides a few young bulls, we sighted a very old single tusker with around 75 pounds on the left side, but no ivory on the right.

The 24th of June was a day we will remember for many years to come. Just before noon we happened upon the track of a single, apparently large bull. We found him an hour and a half later, fast asleep and snoring! For those of you who take this as a hunter’s yarn, I have proof of the story, as I took plenty of pictures of that elephant lying on the ground! As we watched him, something must have alerted him, because he unexpectedly stood up and sleepily checked the situation while we made a slow, but probably too noisy retreat. We stopped moving, he didn’t notice us, and soon lay down again and resumed his snoring! I’m sure that even in the colonial days, only very few witnessed this intriguing scenario.

The next day, which was not typical of this safari, we didn’t find any worthwhile tracks, although we drove almost up to the Botswana border. But on our way back to camp, we spotted a group of elephants with one bull that made our pulses beat faster. It took us only a quarter of an hour to approach close enough to take a good look. This elephant had a huge body and long, thick and even tusks. He definitely looked like an 80-pounder or more. For the first time on this hunt, Uli chambered a round. We took many pictures, while Felix carefully checked the bull, discussing its age with Robert and Kashe. Finally he said: “We’ll let him go. He’s too young, plus he has the potential to become a 100-pounder.” We all agreed and could then relax and enjoy the magnificent sight.

Not tomorrow – the day after tomorrow

When on our way back to camp three days later – we had been following some young bulls for hours – we discovered a huge elephant some distance away. We wanted to take a closer look, but made too much noise, or possibly the wind had changed direction. The elephant disappeared into the bush. It was already five in the afternoon, too late for us to pick up the track that day. Frustrated we headed for the truck. Felix asked his tracker: “Kashe, will we get him tomorrow?” The Bushman pondered his answer for a few seconds, then replied: “Not tomorrow. The day after tomorrow.”

With high hopes we took off the next morning, following the track. We went through areas with thickets and the ground became more rocky and stony by the metre. Up until now, our trackers had never lost a track, but on this hard ground they lost it after an hour, since plenty of other elephant spoor made tracking even more difficult. They put down their baggage, asked us to wait, and fanned out. Robert was the last one to give up, returning after five hours. The track was lost. For the first time all six of us were disappointed, but Felix tried to cheer us up: “There are three waterholes in the area. It’s likely that he’ll drink at one of them during the night. We’ll check them in the morning. This is our best chance.“

And Felix was right. The next morning, after checking two waterholes with no luck, he came back grinning, thumbs up, from the third one. “He was here last night to drink.” That day the track was easy to follow. Robert, Kashe and Kxao were fast on the trail, almost running. After only two hours we had the bull in view. A great sight! The huge bull was feeding, completely at ease, in open terrain. Again judging the bull took time. After Felix had discussed his thoughts with the Bushmen, the verdict was: “We are sure he is an old one.”

After approaching the elephant up to 70 metres, Felix and Uli took the lead, the trackers staying back, while I followed the hunters at a distance of about 20 metres to take photographs. The bull was now moving away slowly, but the two soon caught up with him again.

“The next morning after checking two waterholes with no luck, he came back grinning, thumbs up, from the third one. “He was here last night to drink.”

The brain shot from the side was somewhat high, but in the open terrain, as the bull took flight, Uli was able to make two more lung shots with his .416 Rigby. We were sure that the bull would be down within a few hundred metres. However, after a short sprint, we saw him disappear slowly into the bush, about 800 metres away. Without speaking, we picked up speed, but were slowed down by the dense bush. During a short break to drink water, Uli muttered: “I’m really not superstitious, but this is my 13th hunt in Africa and today is the 13th day of our safari!”

Felix cheered him up with: “He has two good shots in the vitals and he won’t get far.” To which I added: “And it’s not even one yet.”

Unexpected charge

In the next thicket the trackers slowed down again and Felix whispered: “Watch out, he‘s close!”

Moments later we spotted the bull in the thick bush about 70 paces ahead, facing towards us. Quietly we eased to the right to gain a better position for giving the coup de grâce, with Felix signalling at me and the trackers to stay back. But like young bird dogs, we warily followed Felix and Uli for another 50 metres.

From where the trackers and I were standing, we couldn’t see the elephant. Then I heard what I believed were two shots as the bush exploded and everyone was running around like hell. After we’d joined forces again and regained our breath, Felix reported: “At 30 paces Uli landed another shot behind the shoulder. The bull immediately charged us. Our two simultaneous shots to the head at 15 paces turned him away only a little. So now we really had to run. Even with a double, there wouldn’t have been enough time to place another shot.”

We sat down on the ground and drank some lukewarm water. The break was short and, strange as it may sound, it was just before one o’clock when we found the bull dead in his tracks. It was indeed a lucky 13!

Felix had been right: the elephant was an old one and carried long, thick tusks, but for the time being, nobody wanted to discuss ivory weight. We sat down in the shade, all of us reflecting on the last few hours.

Only the next morning, while the Bushmen from the neighbouring settlements were collecting the meat, did Felix size the ivory. The length of the tusks was almost 2 metres, and their circumference 52 cm. Three days later Uli and I flew back, while Felix was leading another dangerous game hunt in the Caprivi. He would return to Bushmanland only three weeks later.

After three long weeks of waiting, he finally pulled the tusks out of the skull. They were 86 and 84 pounds respectively, and 193 and 184 cm long.

With kind permission of JAGEN WELTWEIT, June 2013

ADDICTED TO NAMIBIA!

_________________________________________

Dear reader,

Allow me to add a few personal remarks on Namibia as a travel and hunting destination. In 1991 – as novice editor in chief of JAGEN WELTWEIT – I responded to an invitation from Volker Grellmann, one of the godfathers of trophy hunting in Namibia, to undertake my first round trip through the former South West Africa. His objective was clearly to lure me to this wonderful country. It was easy. Since then I’ve fully succumbed to Bacillus africanus! Thank you, Volker!

Since 1991 I’ve traveled in most of the countries in Africa that offer trophy hunting, 25 times in total. Eight of these times I hunted in Namibia, not counting the elephant hunt chronicled in these pages. I have visited no other African country this often, and on every trip I discovered something worthwhile, such as friendly people, breathtaking landscapes and exciting hunts on ranches, in conservancies, and in big game concession areas.

Compliance to the principle of sustainability is a complete success in Namibia. This country can indeed take a vanguard position as an example for many other African countries. Only when game is of value for the local population, will it be possible in future to conserve wilderness areas with their flora and fauna. So the principle is: use it or lose it! Since the ban on trophy hunting in Kenya 35 years ago, that country has lost more than three quarters of its game population. Unfortunately and against the better judgement of many, Botswana is currently following the same route.

My impression is that in the well over 20 years I’ve been hunting in Namibia, the game populations in your country have, due to excellent game management, increased remarkably – and I’m not referring to releasing non-indigenous species on high-fenced farms. Today sustainable hunting adds to the welfare of many people, especially in rural areas. I hope it will stay like this!

Andreas Rockstroh