Age Related Measuring System

January 14, 2019

A Memorable Experience Finding That Buffalo

January 14, 2019I was born at Otjivasandu, the first white child at the remote ranger station in western Etosha National Park. I grew up in the bush, hunting for insects with my pet bat-eared fox. I went to boarding school at a very young age, but was fortunate to go on my first bow hunting adventure with three Ju/hoansi men from a settlement called //Auru, who had promised my father before I was born that they would teach me how to hunt in the traditional way with a bow and arrow. They knew my father, Allan, when he was a senior ranger, tasked to develop the Khaudum Game Reserve which back then was known as Bushmanland. When bow hunting was legalised in Namibia in 1998, my father bought his own piece of true wilderness, far from civilisation, with a large population of indigenous species. He invited his Ju/hoansi friends from //Auru –/Gou, Tsissiba and /Xau – to become trackers on Sandveld Game Ranch. This is how I was introduced to hunting with bow and arrow, as a teenager on school holidays.

The hunters prepared the arrows and we set out into the dense Terminalia shrub looking for fresh animal tracks. After two hours /Xau whispered, “Fresh gemsbok tracks! There are three, and they are feeding. Look, they are not walking single file and their spoor in the sand are not deep. They are moving slowly. We will track them.” /Gou told me to walk behind him and make sure that I step on his tracks to avoid stepping on a snake or sticks and leaves. The smallest noise alerts the animals, he said. After following the track for some time, the three hunters abruptly sat down and indicated to me to do the same. They pointed ahead – and there they were. The stealthy stalk started to within 40 metres when Tsissiba instructed me to stay with him and allow /Gou and /Xau to make the final stalk.

The two hunters removed most of their clothing and slowly but meticulously approached the gemsbok. “Look carefully in the direction of the gemsbok”, Tsissiba said. “You will see the head of one of the hunters peeping over the grass to see where the gemsbok is, to estimate the shooting distance, and look for a shooting lane.”

I look on in amazement as suddenly the head of one of the hunters appears above the grass. The gemsbok carry on feeding, unaware of the danger. A few seconds later we hear the faint sound of a bowstring, and the gemsbok scatters in all directions. The crashing noise they make running through the bush soon fades in the distance as /Gou and /Xau stand up, indicating that the shot placement is high in the neck. The poisoned arrow hit its mark after a shot from a mere 15 metres.

We all sit down to rest, waiting for the poison to work its way into the animal’s bloodstream and take effect. /Xau says it is time for a drink, but they did not bring water. Close by he shows me a downy stem, about 20 cm tall, rising from the sandy Kalahari soils. “Dig down alongside the stem,” he says. “There is a bulb at the end of the stem.” I remove the bulb of a perennial herb, which the San call bi. /Xau planes the herb, which the San call bi. /Xau planes the bulb with his spear blade takes the shavings and squeezes them in his hand, allowing the water to run into his mouth. “Try it, Wayne,” he says as he hands me some shavings. “It is bitter, but not too much, and it will quench your thirst.” After this lesson, it is time to get going. bulb with his spear blade takes the shavings and squeezes them in his hand, allowing the water to run into his mouth. “Try it, Wayne,” he says as he hands me some shavings. “It is bitter, but not too much, and it will quench your thirst.” After this lesson, it is time to get going.

“You take the track once I have identified the one that was shot.” Bending down, he retrieves his arrow shaft. “See the pattern of the sinew that was used to bind the shaft at the nock? It is mine. The short shaft, which is smeared with poison and attached to the broadband, has penetrated the neck of the gemsbok. This is the shot animal’s track. Here, you take the track.” With the help of the hunters, I begin to spoor.

The San Hunters prepare the arrows with poison.

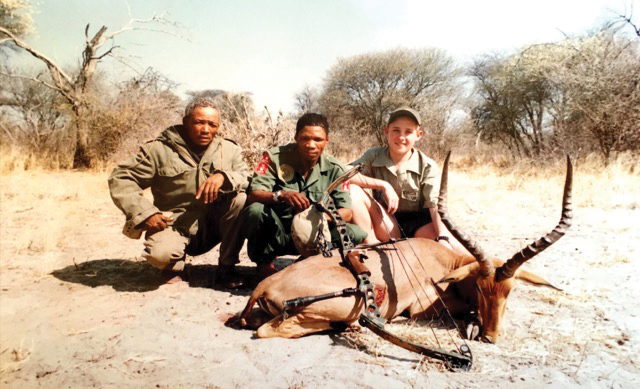

An old Mathew’s Q2 compound bow, with which I took my first animal with guides /Gou and /Xau.

Soon the tracking becomes easier as they explain what I should do – look down, look up, see the tracks ahead. Eventually, they point out the shortening stride and zigzag walking pattern in the spoor as the gemsbok often stops to rest. Evidence of a confused and weakening animal.

Two hours later /Xau says, “He is close. Be alert and look ahead. You must try to see him.” Just then I stop and all of them simultaneously point at a light grey shape, head down and horns distinctly shining in the midday sun. “The gemsbok is weak and confused”, /Xau says. “Come, bring the spears.” /Gou walks in front and moves in slowly. With one accurate throw, the spear penetrates the lungs of the gemsbok and he drops down in the sand.

/Xau removes the arrowhead, carefully attached to a carved giraffe bone, from the centre neck area of the gemsbok. An accurately placed shot.

Handing me one of their traditional knives, the skinning begins. We remove the skin and then disembowel the animal. We cut the meat into long strips and remove the heart and liver. They light a fire using their traditional sticks. Tsissiba cuts the liver and heart into pieces and carefully places them on the glowing coals. “Come and eat. It is your first true hunt, and this is Ju/hoansi tradition.”

While we ate /Xau explained to me that the Ju/hoansi people hunt to eat and that they use the entire animal – the meat, the skin for clothing, quivers and bags, and the horns to make curios. Nothing goes to waste. “You must remember this, one day when you guide bow hunting clients like your father. Make sure they hunt in this way. One very important part of the hunt is that one must show respect for the animal. Teach your clients this one day.” A thought that has stayed with me ever since.

They made a leather bag from the gemsbok skin and put as much meat as possible into it. A branch was cut from a tree and the bag hooked in the middle, allowing two hunters to carry the load. Tsissiba then hung the remaining meat high up in the trees. “We will come and collect the rest of the meat in the morning.” At dusk, the hunting party arrived in camp singing a hunting song and imitating the straight horns of the gemsbok with their outstretched arms. The following day we went back to the site to collect the remaining meat hanging from the trees and carried it back to camp.

That same week we built a natural brush blind at a game path some 200 metres from the waterhole. “Take your bow”, said /Gou. “Let us go hunting. It is your turn now.”

With my old Mathews Q2 compound bow, its draw weight reduced to 55 pounds, we set off. After the second day, while lying in ambush, an adult impala ram walked along the game trail passing 20 metres from the blind. “Get ready”, said /Gou. “I will stop the animal, then you shoot.” When the impala was in range, /Gou made a faint grunt. The impala stopped in its tracks and I released the arrow. It penetrated the shoulder, the target known as the “vital V”. Within 40 metres the impala collapsed.

With respect and a sense of sadness, I approached the animal and knelt over it, caressing the beautiful red coat. My first animal hunted with a bow and arrow. We took the meat back to camp. It was enough to feed everyone. The skin and horns are still my treasure to remind me of that hunt.

Now that I am a professional hunter, I cherish and share the insights those three hunters gave me, although they did not use my language to explain it: the animal had a fair chance, and I hunted it in the bush where it belongs. They also taught me to have respect for animals.

Allan Cilliers, game ranger to professional hunter, with son Wayne following in his footsteps.

This article was first published in HuntiNamibia 2019.