Nature’s ballet

August 22, 2017

The role of hunting through the eyes of a non-hunting conservationist

August 22, 2017I would select a rosette on his shoulder as my target and slowly squeeze the life out of the trigger. What a perfect setup, I thought. e weapon’s fore-end was cradled by a V-shaped sandbag resting on two horizontal camel thorn limbs wired in place on each end to steel fence posts driven deep into the earth, and the rifle’s balance point nestled in the top strap of an aluminium tripod shooting stick. Without real effort I felt the metal of the trigger on the tip of my right forefinger and gently pressed it. “Boom”, I said softly to myself, imagining the cat with his nose in the fatty flank of the warthog we had meticulously anchored to the tree. Lifting my head I turned to my left to catch a broad smile on the face of my professional hunter and friend, Kurt Duval, owner of Namibia Hunting Impressions. With a wink I whispered “perfect”. is had been a dress rehearsal, but as important as if it were the real show.

Kurt had done his job and I was eager to do mine when the opportunity presented itself. With leopard hunting the attention to detail must be all-inclusive and the execution of the plan meticulous. Kurt was smart to put me in the chair to get a feel for the setup and to mentally execute the shot. Having hunted in seven countries on the African continent I can attest to the expertise and professionalism of the Namibian PHs I have hunted with in the past and I am honoured to call a number of these professionals my friends – those who exemplify the character and dedication of the consummate PH.

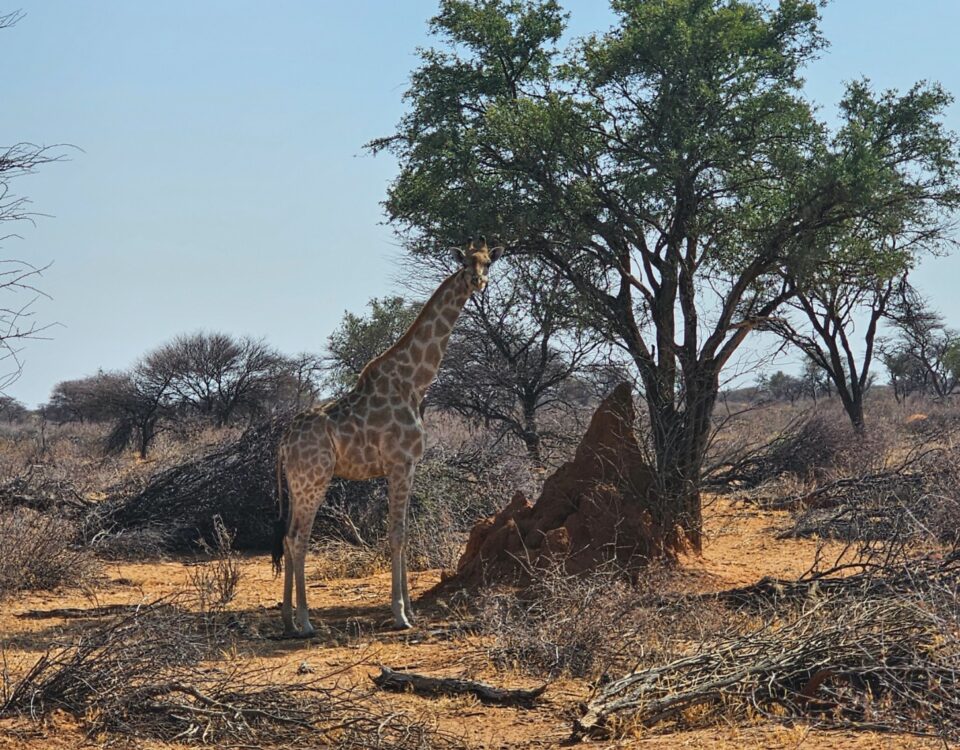

Planning for this hunt began the previous year when my wife Betsy, Kurt and I had been stalking two large kudu bulls late one afternoon on their farm Wolfsgrund in the central east of Namibia. e spoor of the front paw of a very heavy cat was left in the red sand. 2016 was to be something of a milestone for me and my African hunting. e trip would mark my 50th African safari in seven di erent countries and my 30th visit to Namibia. At that moment, when I saw that spoor, the leopard became the focal point of my 50th safari.

I fell in love with the “Jewel of Africa” in July 1987 during my rst visit to farm Lichtenstein Nord, owned by Uli and Anne Rusch. It was through their generosity that I, as a young husband and father with very limited “disposable” income, was able to visit Namibia in those early years. We have become family as a result.

Over the years I have met many wonderful people and I have had many incredible hunting adventures in former S.W. Africa. I remember the deployment of UNTAG and the first general elections. I remember a night at Okaukuejo having a sundowner with Volker Grellman and Peter Capstick, and talking with them about the elephant video they were working on. I will never forget the incredible dune trip across the Namib, or the gin clear waters of the Okavango. The sun shines differently on the African continent. Africa’s smells, sounds, and vistas are unique. Each time I come for a visit a primal feeling stirs deep in my soul that tells me I have come home.

During my 2014 visit we radio-collared a 64 kg male leopard on the Rusch farm in the Khomas Hochland, from which the researchers are still receiving data. e look on Betsy’s face as she actually got to “pet” a live, albeit tranquilized male leopard spoke volumes regarding her newly found appreciation for wild Africa. Since then two additional leopards have been caught, collared and released on the Rusch farm. I understand that a great deal has been learned about leopard habits.

In those early years it was rare to see leopard sign. Something that is now a common occurrence across most of Namibia. It is the result of the excellent management of game animals practiced by the country’s land owners and awareness of its value and importance.

The trail camera had shown the images of a very large male feeding on our offering. Two days prior to my arrival this cat had killed and partially eaten a bovine calf, which Kurt had accepted from the land owner as our starter bait. We were actually hunting on a neighbouring farm. Kurt had successfully hunted on Wolfsgrund the previous month and his European client had taken a huge male leopard. at calf was now history and we replaced it with a fat female warthog. The camera also told the story of a female leopard feeding, as well as a brown hyena’s investigation of the bait site.

Each time bait was replaced we followed a specific routine. There was always a new scenting of the area using the intestines and offal on the tree and around the bait site, preceded by a “drag” in all directions.

August can be windy with weather fronts moving in and out on a seemingly rhythmic basis. is year was no exception and we had to be ever conscious of the wind direction. We had avoided the temptation to rush this. Patience was our ally. We did not sit in the blind for the first few days. It was important to get this feline comfortable with our setup.

Knowing that this cat had been hunted the year before by another well-known PH meant it would not be an easy mark. Even though we had another male occasionally feeding on bait number two, we decided to concentrate on the one with the big paw. e odds were against us, but what a challenge this hunt presented!

Our first sit in the blind came on day five. Anticipation was at its peak and all my senses were on alert. is cat was feeding earlier each night. We needed him on the tree during daylight hours. Unlike other countries, Namibia does not allow artificial light and basically NO shooting from half an hour before sunrise to half an hour after sunset. is is the proverbial “one hand tied behind your back” scenario for leopard hunting. But it was not a problem as I knew the rules going into the fight.

Day seven’s check of the bait and trail cam showed a beautiful photo of Spots standing on the limb over the warthog in broad daylight. Now the dilemma of when to sit became paramount. We could not risk a late night or very early morning entry into the kloof and into our blind, possibly alerting a feeding leopard. We would have to sit the entire night in order to be present as the sun rose and he came to feed.

At 4:30 pm we entered the kloof. Naftali, our Kavango tracker, suddenly stopped and peered up the valley toward our bait. Something was sitting next to the bait. This something was big and black. I heard Naftali tell Kurt that it was a bat! “A bat?!” How large are these bats? It must be Count Dracula! As it flew off towards us, I could see it was a black eagle. Later I was told that the Okavango has large bats indeed. We entered the blind prepared to be ever vigilant with a sincere hope that our cat would feed in the next two hours. Otherwise it would be a long night.

At 6:15 pm we heard a cacophony of chatter from the rock hyrax. Was the guest of honour coming to dinner? My pulse quickened as my ears strained for every sound. Kurt looked me in the eyes and I noticed an upward crease in the left corner of his lip. He held back a full smile as did I. Optimism permeated the hide.

Hurry, I thought, it is going to get dark soon. A bit more talk from the elephant’s closest living relative, and silence encapsulated the early evening again. We sat without a whisper for the next eleven hours. Daylight slowly filtered into the canyon about 5:30 am. Fighting the urge to sleep, my eyes strained to see the bait tree.

With each passing minute a hazy collage became increasingly clear. A voice in my head was attempting to summon our cat to the bait tree. Using all my powers of telepathy I willed this leopard to a certain destiny, but to no avail. Easing my face onto the rifle and peering through the scope, I could easily make out the bits of offal still stuck to the bark of the tree. I was ready, but our cat wasn’t.

At 8:30 am we radioed Kate at the farm for a pickup. It would be 45 minutes before she arrived and I attempted to “walk off” the stiffness that had set into my legs from the nearly 15 hours I had spent in a seated position. The fresh spoor of a brown hyena along the koppie leading toward our blind, explained the excited hyrax and the warning chatter we had heard from them in the early evening.

Over the next three days our cat never came to feed. We freshened the bait and nurtured an optimism that all true hunters possess. A hunter’s quarry must have a chance to escape and never show; otherwise the effort is not truly hunting.

Lady Luck has smiled on my hunting endeavours many times. On previous safaris I have taken two leopards incidentally when hunting plains game. I had never baited a leopard or sat in a blind for one, prior to

this hunt. is time I paid my dues. We spent a total of 47 hours in that blind, mostly without speaking a word. At times there is an uncanny understanding between hunters. One almost knows what the other is thinking. It was that way with Kurt and me.

The hunting gods willing, there will be another leopard hunt for me. It will take place in Namibia and I will be optimistic about my chances.

This article was first published in the HuntiNamibia 2017 issue.