Successful hunting is mostly a case of making the right decisions at a specific moment in time. These may include: deciding what gear and which calibre rifle to take to the hunting field; in which area to hunt; what the target species will be for a specific day; which specific animal to target in a group of animals; which approach to take to arrive at a shootable position in relation to the quarry; what stalking method to use at what point in the process; establishing which way the wind is blowing; and what distance to compensate for when finally taking a shot. The hunter does not often get the opportunity to correct his decisions.

Photos ©Paul van Schalkwyk

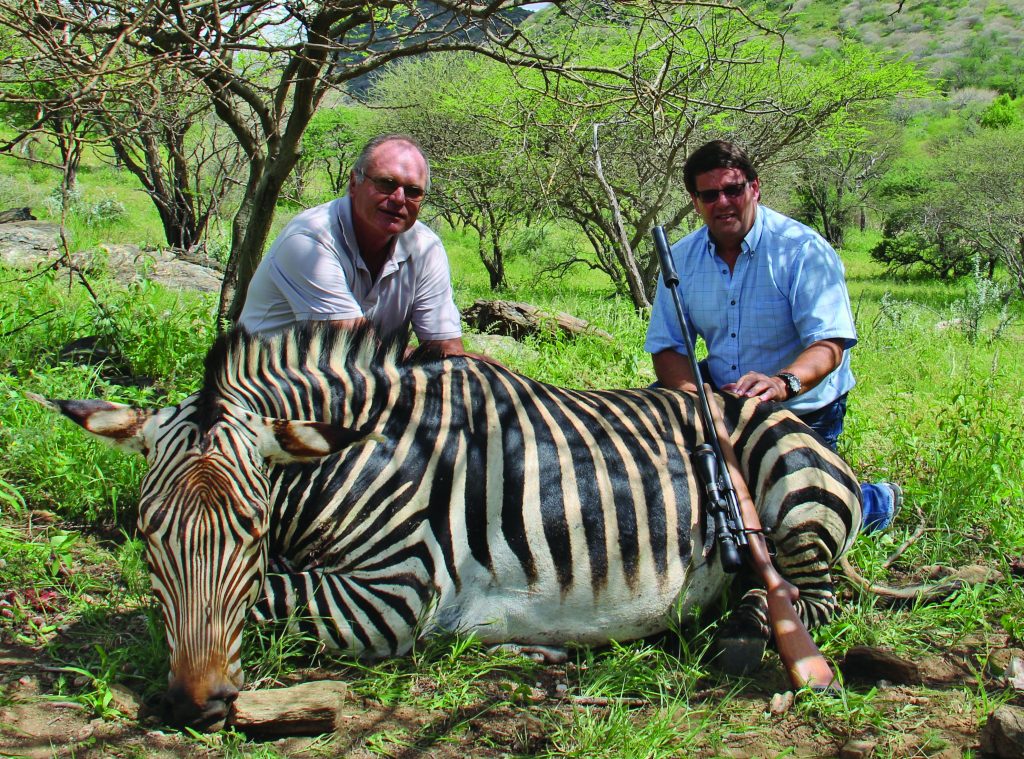

Piet van Rooyen

W e were hunting on Farm Kaujetupa in the mountains of the Khomas Highland west of Windhoek, specifically looking for mountain zebra. I was hunting with the farm owner, my lifelong friend Ben van Rensburg. I wanted a zebra for two reasons: firstly a good, prime-grade skin for a bedroom carpet and secondly a good stash of fat zebra meat for my kitchen larder. Zebra meat is, not without reason, known as one of the best types of venison available to the discerning taste buds of a connoisseur. The late Braam Kruger – chef and cuisine-aficionado, popularly known as Kitchen Boy – rated zebra meat in his book Provocative Cuisine as the best-tasting game meat available, provided that the yellow surface fat is removed from the meat soon after skinning. Zebras also look good to eat from a distance: fat, nicely striped, well-rounded. There is a widespread belief that zebras never get thin, not even in times of severe drought. Another rumour has it that a zebra can die of hunger even when it looks well-fed because it does not have the capacity to re-absorb its fat layers in times of need. We disregarded several good-sized gemsbok grazing on the mountain slopes around us. Our target was a good zebra. I specifically wanted a dark-coloured skin to go with the colour scheme of our bedroom at home. Zebras have no measurable trophy characteristics and trophy hunters visiting Namibia mostly hunt them as a bonus to the normal trophy package. The skin, because of its beauty, however, remains a sought-after keepsake of a memorable African hunt. Sometimes zebras are hunted as bait for a leopard hunt, where these are available on tag. I, however, have great respect for their wiliness and tenacity and find a great deal of satisfaction in a successful zebra hunt itself.

Hartmann’s mountain zebra (Equus zebra hartmannae) is well-known for its adaptation to mountainous areas, where it thrives in a rocky habitat. It is amazing to see where these animals manage to find a foothold between the rocks and boulders of the Khomas Hochland, often running at speed over terrain much too rough for even the best four-wheel drive vehicles to follow.

While trying to bypass the small groups of gemsbok on the farm we could see many fresh zebra tracks in the game paths around us. We were therefore sure that we were operating in the right area. It was just a case of patience and perseverance in order to find our quarry. Suddenly, on reaching a specific mountain ridge, we could see two groups of zebra grazing below us, one group on our extreme left side and the other way down on the right. We had a problem: which one was the best group to target? A quick scan with the binoculars indicated that each of the groups had a shootable dark-skinned individual in its midst. The group to our right had a mature dark-skinned mare and the left-hand group, although further away, had a very good stallion. From that distance, I could not detect any blemishes on either of the skins. Stallions often fight amongst one another and, in order to obtain a good skin, it is necessary to inspect the quarry very closely before taking a shot.

Ben reckoned that we should go for the mare on our right. She was nearer to us, about 400 metres away. The wind was in our favour. If we back-tracked a 100 metres or so we could use a small kloof to approach that group. The kloof was thickly overgrown with blackthorn bushes but we would be able to wind our way through them. These would also provide some extra cover for us during our approach. Slowly we went downhill, continually testing the wind direction in the changing eddies bouncing off from the sides of the kloof. We could not see the zebra from where we were, and we could just hope that we were doing everything right for a successful approach. Normally, I am able to focus properly on the intended quarry, but this time the image of the dark stallion kept coming back to my mind. Were we right in letting him go?

We were already half an hour into the stalk when suddenly, with a sinking feeling, we could hear the herd of zebra thundering away through the length of the stony valley. We realised that what gave us away was the same sound effect we could hear now, on a much-amplified scale: crunching down the quartzite surface of the kloof we were making such a noise that the zebra could not fail to hear us clearly. They decided to depart, not waiting to find out whether these were friends or foes noisily making their way towards them.

It was late afternoon already and we should probably call it a day, but I had a feeling that the stallion was intended for me, waiting on the other side of the ridge. “Let’s go see,” I said to Ben. He nodded in affirmation. We slowly worked our way back. Upon reaching the top we found the earlier group of zebra, now much closer, grazing up the slope towards us. Light was fading fast and we had no clear approach to come closer to the group. The distance was some 300 metres downhill. At that moment the stallion started moving – straight up towards us. Since I did not have a rangefinder I had to judge the distance offhand, but fortunately, I remembered not to overestimate the distance in shooting downhill. I lined up my rife scope exactly at the point where the stallion’s neck joins the chest and slowly squeezed the trigger of my Heckler and Koch .308.

As if in slow motion the stallion fell to its knees, then slowly stood up again. The sound of the shot must have been defected by the height above them, for the other animals were just standing around, looking at the stallion as if perplexed. The stallion walked a few metres and then slowly fell over once more, not to get up again. Ben and I looked at each other with a sense of accomplishment. We shooed away the other zebras and walked down to the stallion. What a magnificent animal! We could carefully roll him down the slope in order to load him up at the bottom of the valley. Although we had to change our target halfway into the stalk, this was a hunt that turned out well in the end.

This article was first published in HuntiNamibia 2018.