…but intriguingly beautiful

Text by Garth Owen-Smith | Main photo Paul van Schalkwyk

Text by Garth Owen-Smith | Main photo Paul van Schalkwyk

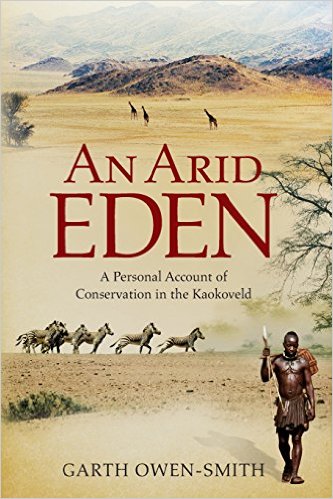

In his book ‘An Arid Eden, a personal account of Conservation in the Kaokoveld’, Garth Owen-Smith tells the story of the early days when the foundation for the ground-breaking approach of community-based conservation was laid. The words below are the introduction of this book.

I n north-west Namibia there is a region of red basalt ranges. It is a landscape of rock: sheer cliff faces, endless scree slopes and stone-choked valleys. Westward, towards the cold Atlantic coast, the mountains flatten out and are separated by broad gravel plains, littered with the debris of ancient lava flows.

It is a place where rain seldom falls, and in most years the earth’s hard surface lies barren and exposed to the baking sun and searing desert winds. The region is stark and hostile, but in the early morning and late afternoon light, when the basalt rocks turn to the colour of rust, and the distant mountains to soft shades of purple and blue, it can also be breathtakingly beautiful.

In spite of its aridity the basalt region supports a remarkable variety of hardy, drought-resistant plants. The stony pediments and less precipitous slopes are dotted with swollen-stemmed succulents, stunted trees and dwarf shrubs that in lean years wither to desiccated tufts of brittle, apparently lifeless twigs. Many of the species here are endemic, occurring only in the deserts of Namibia and south-western Angola. Amongst them is one of the world’s botanical wonders: Welwitschia mirabilis, a prehistoric cone-bearing plant consisting of just two giant, tentacle-like leaves growing from a gnarled and contorted woody stump.

Eastward, where the rainfall is slightly higher, the basalt ranges rise to over 1 500 metres above sea level. Here mopane bushes dominate the valleys, growing taller along the banks of rocky channels that drain the hill slopes. Although they flow only after heavy storms, these watercourses converge into dry riverbeds that traverse the gravel plains, creating arteries of life-supporting vegetation deep into the Namib desert. In a few places where the underground water table is close to the surface there are also groves of graceful euclea trees and leathery-leafed salvadora bushes that provide shady refuges from the tropical sun.

When heavy rain does fall, the basalt region undergoes a dramatic transformation. From the shallow soil between the stones long-dormant seeds of annual grasses and forbs germinate and within weeks paint the valleys emerald green, in striking contrast to the red-brown scree on the hill slopes. The brief availability of moisture in the soil also enables the woody plants to produce new leaves and blossom. And with this abundance of fresh growth, insect populations explode, rodents and seed-eating birds multiply exponentially, and all the desert animals grow fat on the bounty of a benevolent season.

But the feast soon ends. Within months the green carpet of grass is bleached to pale yellow by the sun and dehydrating winds that in winter sweep down from the interior plateau. As the land dries out once more the ephemeral plants and insects die, but not before producing countless seeds and eggs to ensure that new generations of each species will appear when thunderstorms once more roll across the desert.

In spite of the very arid climate those basalt ranges are well endowed with small springs that provide drinking water for a remarkable array of large mammals. And because the volcanic soils are exceptionally fertile the grass that grows in the good seasons is cured into standing hay, thus retaining its nutrient value in subsequent years when little or no effective rain falls. This carry-over of high-quality grazing is crucial to Hartmann’s mountain zebra, the only exclusive grazer permanently inhabiting the region, and together with its ability to migrate large distances and climb the steepest slopes, enables it to survive the frequent droughts.

Like zebra, gemsbok and springbok also congregate in large numbers to feed on the green grass that grows wherever heavy showers have occurred. However, when it dries out both species can switch to browsing the leaves of the desert shrubs, which combined with their low drinking requirements allows them to penetrate deeper and remain longer in the true Namib, one of the driest habitats on earth.

Because they are exclusively browsers, kudu and giraffe prefer the more wooded areas further inland, but after good rains in the pre-Namib – the belt of plains and rocky ranges along the edge of the desert – kudu move westwards to exploit the flush of new growth there. Giraffe also follow the larger watercourses that traverse the basalt region far into the desert, and small groups may be seen striding sedately across the virtually barren gravel plains between them.

The herbivores that occur here in turn support a full spectrum of large predators, with prides of lions hunting the hills and riverbeds, cheetah coursing their prey on the gravel flats and leopard stalking the rocky gullies and more rugged mountain slopes. Packs of spotted hyena clean up behind the big cats, but also run down their own prey when the opportunity arises, while jackals are ubiquitous. Man has long been a predator here too – in the past as a hunter-gatherer – killing game for animal protein and fat, but in more recent times with a commercial incentive as well.

Most remarkably, elephants also inhabit the basalt ranges, finding sufficient sustenance in the bark and leaves of the sparse desert trees and shrubs to maintain themselves. On their wanderings in search of food and water the pachyderms have worn a network of paths through the region, some of which go over the highest mountain passes. During the cool dry season a few herds also move down the larger riverbeds deep into the desert, quenching their thirst at remote springs whose whereabouts has been passed down through the generations.

In the 1960s the north-west contained Namibia’s biggest population of black rhino, but in little more than a decade the sky-rocketing black market price for their horns brought the species to the brink of extinction here and throughout most of Africa.

Featured in TIME magazine some twenty years ago under the title ‘The World according to Garth’ and regarded in the industry as a ‘conservationist extraordinaire’ and ‘the man who saved Kaokoland, home to Namibia’s desert-adapted elephants’, Garth Owen-Smith is a gifted writer with a highly unusual and gripping story to tell. He provides answers to important questions distilled from forty years of dedicated experience in the field in Namibia’s Kaokoland, introducing a vivid cast of characters in what can well be considered a blueprint for successful conservation in Africa.

This article was first published in the 2016 English edition of HUNTiNAMIBIA.