Text Basie Maartens

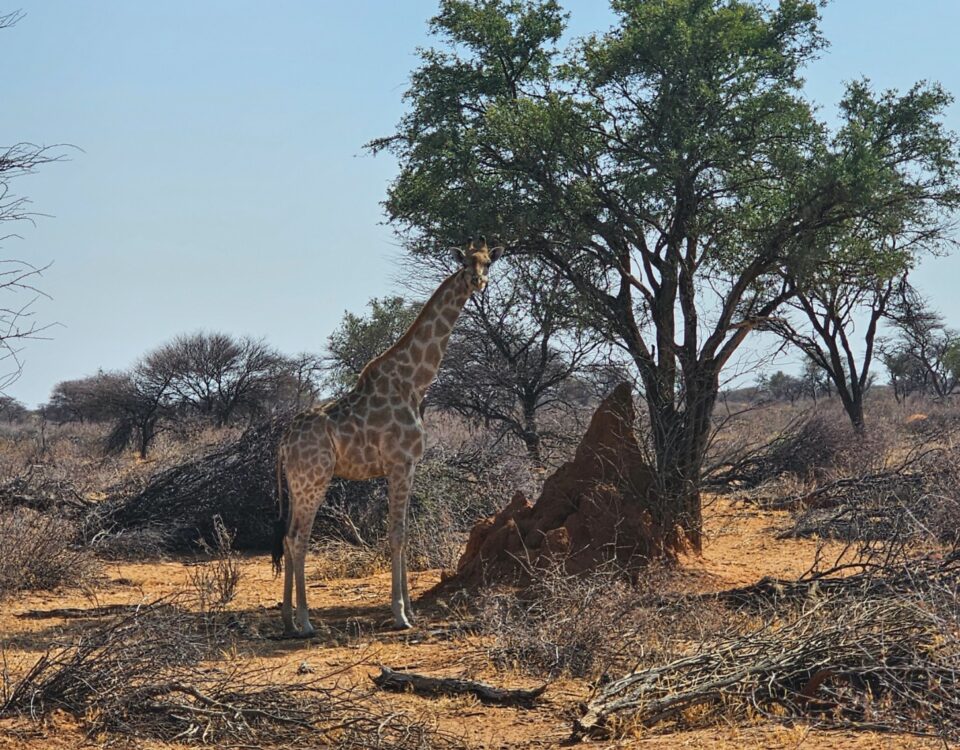

Kaokoland – Stark and hostile

April 14, 2016

Collar me crazy

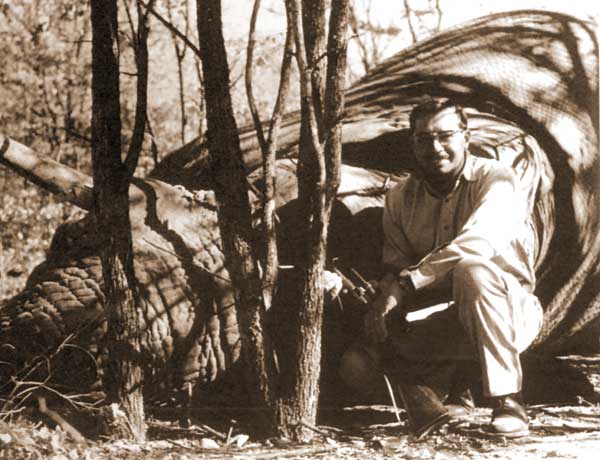

April 19, 2016Main photo: In 1965 Bushman (San) often joined me on hunts in the Sandveld. They could down a buck with bow and arrow.

The eland is a big, fine antelope and much more agile than its 1,500 pounds might suggest. Because its tasty meat is often compared to beef and due to its docile bovine manner, it does not carry quite the characteristic sporting cachet of other antelope species, but do not underestimate the eland. They will run at a fast trot all day long to leave you and your client far behind or will jump a six-foot obstacle with the greatest of ease.

N amibia’s Sandveld area (whose north-eastern section borders Botswana) is typical eland country – big trees, tall bush and sand, sand, sand. Not a hill in sight, not a rock to throw at a snake, of which there are many. One thing I did like about the Sandveld was the occasional presence of open pans that were filled with water. The hunter could check around these pans for tracks because that was where everything came to drink and that was where the hunter made ready, for so much depends on tracks. Tracks are the road map for the day, telling us where to go and what to do. Hopefully they would lead us to our goal, that heavy-necked animal whose tufted boss has spirals coming out of the skull.

This particular eland hunt, which I remember very fondly, took place a long time ago, in 1965 when I was operating throughout the whole country. Bill Picher of California was with me and we headed out beyond the “red line”, that imaginary line where the farms end and there is just wide-open country beyond, with no habitation except for a few nomadic San. Without them we would not find what we were after, so we were very happy to see about half a dozen San hunters squatted on their haunches when we arrived at the first waterhole, waiting for us. One of them, who seemed like the leader, spoke with much gesticulation and verbal sounds of which we understood very little, but the message was very clear: “Follow us to see many animals.” I did make out the word mpofu, and to me that meant eland, so I was quite happy to follow them wherever they led us.

There were no Eland tracks leading from the waterhole, but within half an hour we came across a game trail that led directly east, about 90 degrees from where we were going. So we made a sharp right turn and followed the array of tracks, which included some very heavy imprints of eland, as well as zebra and impala. But only one kind interested us, and they were getting clearer and fresher.

We realised that the eland were not very far ahead of us. The San fell back so Bill and I were the only ones following the tracks, now on a path that we could not mistake anymore. Maybe we were too confident about seeing eland just around the corner, because we did not see anything for another 15 minutes, and I stopped to let the leader of the San hunters catch up with us. But he just shook his head and indicated that we had to keep moving. So we marched on. I knew we were in for a long haul when the leader set a pace that was rather taxing on the leg muscles. The San were far fitter than we could ever hope to be, and Bill and I were discovering that as the day wore on and the sun shone mercilessly on our backs.

It was about 4:30 p.m. when we first saw signs of wildlife again, and we dropped to a crouching walk. Signs of animals were all around. We stopped and waited for something to happen. It was not long before we spotted what looked like an eland bull coming through the bush. This was what we were looking for, but we only caught a glimpse of it.

As the bull moved, we scuffled along to keep up with him, until he came to a halt at a lush green bush and started nibbling. He paused just long enough for Bill’s .338 Winchester to speak loudly and the bullet smacked into flesh and muscle. It took only seconds for the massive body to collapse, much to my relief. I did not want to have to start a search for a wounded animal that could still be hard to bring down. We now had a carcass on our hands, which was going to take most of the night to skin, butcher and carry back to camp. But there were six happy San hunters to help and when Bill and I left them to carry on with it, the first fires were already burning to receive the choicest bits of meat.

We struck out for camp, retracing our footsteps on the same trail along which we had come. The sun was already setting, and it was not long before it sank below the horizon and total darkness descended. In this part of the world there is very little twilight, and soon we would be fumbling to find our way in the darkness. Well, we must have been living right, because within half an hour a full moon rose from behind the treetops and rapidly grew until we could see our own shadows on the sandy path before us. Although it took another hour and a half, we reached our primitive camp in good shape and spirits, immediately strengthened by building our own fire and settling down to a well-deserved libation and a toast to our good luck.

It was well after midnight when the San rolled in, chanting their “click” song and apparently still ready for more eating. They surrounded the fire they started with coals from ours, which was now rapidly dwindling to mere embers. They had left one man behind to look after the remainder of their meat, which they had hung over tree branches out of the hyenas’ reach, and brought with them the horns and skin and as much meat as they could carry. The moon was already nodding to the west when I finally fell asleep, tired from a long day’s walking but content with the outcome – the fact that we had bagged a coveted trophy.

This article was first published in the 2016 English edition of HUNTiNAMIBIA.