Indigenous Species and their natural distribution in Namibia

January 7, 2019

My first Namibian Experience with Bow and Arrow

January 7, 2019In bright sunlight, the leopard slowly and quietly stalks up to a waterhole. He calmly sits down and watches the surrounding bush, alert and ready, his ears catching even the softest of sounds. When he spots a hartebeest approaching, the big cat slowly bends down between dry branches on the ground, camouflaging itself as a picture of placid serenity. The antelope either has not noticed the cat or is not afraid – instinctively sensing that leopards generally do not take adult hartebeest as prey. When the hartebeest bends down to drink, the leopard takes its chance and lunges forward. The hartebeest reacts swiftly and runs off. The leopard, unsuccessful at its stalk, slowly moves towards the water. A few moments later he is joined by a slightly smaller leopard. Both cats drink and watch each other surreptitiously. Eventually, they move off, each in their own direction. This description by Dirk Heinrich is a sight to behold. Only a camera trap a few meters from the waterhole is witness to the encounter.

Danene van den Westhuyzen

T he farmer sees the pictures days later and is surprised that there are two leopards in that particular area, and that they are active during daylight and early in the morning.

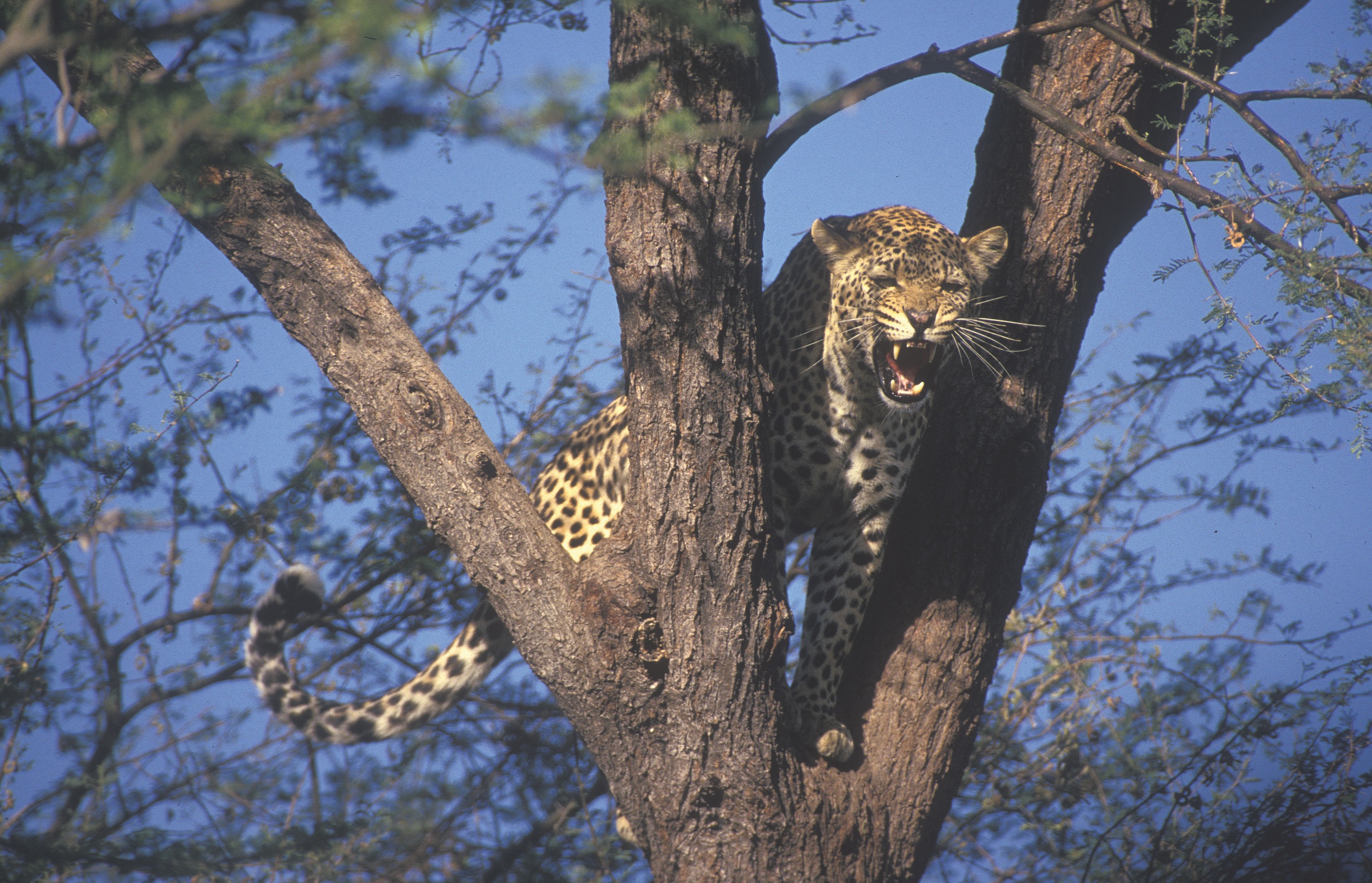

For any nature lover, this is a sight to behold. Many tourists and animal lovers spend hours in the African bush, hoping for that chance encounter with this amazing creature. Known as the most efficient predator in the world, the leopard is a cunning and skilful hunter, one of the big cats that play a big role in the beautiful balance of nature. Its beauty lies in its dark rosette markings on a yellow-brown pelt, in its shy and solitary movements, in its feared encounter with any man or beast, and in its deep and rumbling growl at night, drifting through the bush, silencing all surrounding movements and sounds.

But, as with most predators, life is a perilous journey and calculated risks have to be taken to be able to survive. Competition in the bush is fierce. Territories are claimed by strong and older males. Natural habitats are constantly changing because of droughts and commercial farming practices, and food sources alter. Mostly, the leopard is threatened by its greatest predator – man. Having to share its territory with humans, whether the human is a selective conservation hunter or a commercial farmer, leopard find themselves in even more delicate settings and try to adapt, hide, and survive.

Namibia is a country which paints a picture of Africa still in its purest form – vast stretches of wild open spaces, healthy and balanced fauna and fora, magnificent free-roaming wildlife still increasing in numbers, a small human population, and a nation and people that treasures its natural resources and is dependent on it. This in itself makes it a first choice for any tourist wanting to explore unspoilt Africa.

But as is the case in all African countries, human-wildlife conflict is one of the greatest challenges that Namibia faces. Our government’s policy is refreshing since our constitution calls for balanced and equal land use between wildlife and the human population. Our people must utilise the land, farm and produce food, but at the same time we must also respect and realise the importance and value of our wildlife.

Our tourism industry depends on this outlook, and our responsibility for Mother Nature and the future of our children and our wildlife rest heavily on our approach and actions.

Most commercial farming practices cannot afford to tolerate the direct competition between predator and livestock. Commercial farmers suffer tremendous financial losses each year through cheetah, leopard and other predators which operate in territories where easy prey like cattle and sheep are present. Farmers have two options: a) Eradicate all predator species on his property through various means like cage and gin traps, poison or shooting on sight, usually when caught at a kill b) Adapt farming methods, if possible, in a way that decreases the chances and success of a leopard to catch livestock, forcing him to rather pursue game. This can be achieved, for example, by moving herds away from areas most frequently visited by the leopard, or adding extra protection to herds, like donkeys or trained dogs which warn and help to protect livestock.

Most measures to deal with this conflict are not always lucrative and at the end of the day, conservation efforts are weakened by indiscriminate killing of leopard. And even if leopards are killed to counter conflict, it usually leaves a vacuum which attracts a new male, and so the vicious circle continues.

The situation is taxing. Both the livelihood of farmers and the conservation of leopards are at stake, and to find a way for both to live together of the same land is an extreme challenge. Controlled and selective hunting practices which contribute to conservation are one possibility. They offer an incentive to the farmer. Instead of killing any leopard on sight, they combine a good farming management practice with an off-take of leopard according to a science-based quota. Trough this method, the farmer at least gets compensated for some losses. Since a court recently found the value of a leopard to be at least N$50,000, farmers will see much bigger value in this divine species than when it was shot and left to rot in the veld.

Hunting quotas have been established as a way to control the legal off-take of leopard, to try and ensure a fair distributed off-take throughout the country and in line with the occurrence of leopard, as well as to exercise strict control and adherence to the CITES regulations set out for Namibia.

As recently as 2012, the last comprehensive leopard census was undertaken in Namibia. These findings, together with previous studies, suggest that Namibia has the highest leopard density in all of Africa. These statistics correlate with the present line of thought gaining ground in Namibia, according to which an increase in the leopard population in Namibia might be one of the primary causes of the perceived decline in the cheetah population, due to the fact that leopards are in the process of taking over territories that have been seen as cheetah habitats for decades.

All this, of course, flies in the face of the commonly held belief internationally that the leopard populations in Africa are facing a steady and steep decline – which has, inter alia, been used by the anti-hunting lobby as ammunition to promote actions to bring about the banning of leopard trophies into certain countries, as well as the proposal to list leopard on Appendix II of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS).

Given the fact that the leopard is a shy, solitary animal, well versed in the art of camouflage, estimates and notions by many uninformed parties as to population densities, habitats, habits and distribution are at best sketchy.

This results in a great many suppositions and assumptions that are currently being bandied about by ignorant “well-doers” as “proof” of an alarming decline in leopard populations. This, in fact, has a directly opposite result of what is endeavoured to be achieved by true conservationists through comprehensive studies and proactive commitments for the further betterment of the species.

Other sources such as commercial farmers, for example, claim that they have noticed an alarming increase in leopard populations with the resulting increase in human-wildlife conflict.

These reports of a dramatic rise in livestock losses brought about by an increase in leopard activity have led to a situation where leopard populations are now possible under threat due to human-wildlife conflict situations in Namibia. This situation has been exacerbated by the severe drought that Namibia suffered from 2015 to 2017. Vast tracts of this country have to recover fully from the effects of this drought.

The Namibia Professional Hunting Association is a major role-player in the protection and maintaining of a diverse and healthy wildlife population and believes it imperative to assure the sustainable utilisation of all game species and their eco-system in accordance with the World Conservation Strategy (IUCN) adopted by the United Nations and as amended in 1991.

NAPHA therefor has based on the 2012 and earlier studies, proactively initiated to contribute to this endeavour even further through a comprehensive, independent and non-partisan study of one of our most valuable natural resources, the African Leopard. This study will advance a full scientific background on the population within the country’s borders, help establish a fair value for the leopard, and assist the Ministry of Environment and Tourism as well as CITES to evaluate and or amend the current criteria and quota settings.

In partnership with the Ministry of Environment and Tourism, NAPHA is undertaking a national leopard census project. It started at the end of August 2017 and will continue for the next 18 months. Various other NGOs, including the Namibia Agricultural Union, have shown their support for this project.

To conserve large carnivores it is necessary to understand their abundance in human-dominated landscapes, which is where the real conservation action is needed through an interdisciplinary and adaptive approach. It is essential that research projects should not only be multi-disciplined but also be based outside protected areas, and they should not just be one-dimensional, i.e. ecology or diet. Therefore, this project should take on a multi-disciplinary approach, inside and outside of national parks by combining ecological methodologies and social science to understand the pressures on and status of the leopard population across Namibia.

NAPHA has retained the services of Dr Louisa Richmond-Coggan to coordinate this project. She has excellent credentials and vast experience in this field and comes highly recommended.

We envisage this project to last at least until December 2018, with a provisional possibility of extending the study or developing it to include more species.

The cost of the project is estimated to be around two million Namibian Dollars. NAPHA will greatly appreciate any financial support towards this project, as well as anyone who is willing to assist with valuable data.

This article was first published in HuntiNamibia 2018.