On the spoor of Buffalo and Elephant in the Zambezi Region of Namibia

January 9, 2019

Rhodesian Ridgeback: The Soulmate of Africa

January 9, 2019As I lay in the open bungalow, listening to the sounds of the night; the ‘laughing’ of the zebra grazing on the fresh green, the occasional lonely howl of the hyena and the ever-present, continuous alarm-like call of the Rufous-cheeked Night- jar, I slowly fall into a lucid waking dream, reflecting on the events of past days.

The hunting guests have left camp and I want to go for the last walk before I too leave for home. We make our way on foot in this dust and smoke-laden atmosphere, past the “boat tree” where the hunting starts in times of a flooding river. Now the river and floodplains are dry and we can quickly cover the burnt reed fields. About halfway to the ponds in the side arm of the Linyanti we notice a herd of elephant moving in from Botswana; they are likely to cross our path and we decide to take a slight detour. Our detour turns into an unpleasant fight through thick reeds until eventually, we find a hippo path, which we follow for a while until it bends away into the wrong direction. We now follow smaller paths, often underneath a canopy of reeds – I cannot help but imagine what would happen if we suddenly come across a lion or grumpy buffalo bull in this thick hell!

Every now and then when the reeds open up a little, I balance on one of the reed ‘stumps’ to try and look ahead for the river. Sometimes I suspect the river but then again I am unable to see the elephant that we hear moving in the reeds to our left.

Soon though, we reach the dry river and follow its course, every now and then looking ahead from the riverbank. I am in high spirits in these beautiful surroundings; flocks of weaver birds pass above us, beginning to settle into the reeds for the night; here and there fresh elephant tracks cross the riverbed, amongst them the impressions of a decent bull. A marsh mongoose scurries away into the river brush as we surprise it on its stroll along the riverbed.

We are close to the small ponds now and from the higher riverbank, I take a look around. The left – southern – side of the river is framed with reeds, while north of the river the reeds are burnt down, allowing for a view far into the distance. A few hundred yards away in the northwest I can see an elephant bull slowly making his way through the floodplains, swirling up a small cloud of ash with every step.

Beyond him in the distance the huge dust cloud of the big buffalo herds making their daily trip from Botswana to the hippo pools. Glassing further to the left I notice a movement – I can see the horns and head of a stately roan bull moving along in a small gully or hippo path.

My soul is at peace and my thoughts wander off into the distance, where lions still roam and old battled buffalo bulls find a last refuge near these muddy ponds that are too small to support the big herds.

On our way back to camp we come across a very good reedbuck ram and although we didn’t see the two impressive buffalo again, I feel lucky and happy to have hunted here.

When Felix took over the concession, buffalo only moved into the area to feed on the crops and antelope like reedbuck, waterbuck and roan were seldom if ever seen. Due to the good relations that have been built with the traditional leader, crops are not planted anymore in this area and even eland, warthog and the scarce bush pig have reclaimed this amazing habitat.

The occasional lion prides patrolling here and the howling of the spotted hyena at night make this a true wilderness area that should deserve the protection from any other use than the occasional hunter- adventurer bagging an old trophy, as we had done a few days earlier.

We had to do some shopping in the morning in Katima Mulilo, and after picking up hunter Uwe and his wife at the airstrip, I am glad that we can finally exchange the crowded, though strangely captivating town on the verge of the Zambezi River, for the bushveld at the Linyanti River. We arrive in camp – which is beautifully set on and around an island – and first of all greet the team of trackers, game guards and camp staff, as well as Danita, who will look after our well-being, and PH Wanjo who is doing his big game apprenticeship here. We take it slow for the rest of the day, going for a walk after the usual test shot.

In the afternoon of the second day, we decide to stalk toward the Linyanti River. After a while, we reach a side arm of the Linyanti and walk in the dry riverbed for a bit. As we come around a bend I notice something lying in a sort of hole in the river. Through the binoculars, I can only make out a grey lump. We slowly stalk on and as we come closer the grey lump gets up and turns into a young hippo, trotting off in the riverbed. The hippo must have gotten lost from the herds when they were grazing at night and will most likely become the dinner of hyenas or lions soon. These are the tough – yet necessary – sides to a drought; over the course of the safari we came across a number of hippo carcasses and there will be many more to follow. Only the strongest will at some point leave the hippo pools in search of other waters and only return when the floods return.

We step up to where the hippo had first been and stand above a small muddy pond in a pit in the river. There are tracks of a big buffalo bull from earlier today – immediately my heart beats faster: this feels exactly like the place an old bull would seek, spend the days in the impenetrable reeds near the river and come to water late in the afternoon. It is too late for action today, but in anticipation of what the next days could bring, we return homewards.

As I suspect that the buffalo bulls will most likely come to the muddy pond in the afternoon, we head towards the hippo pools the next morning. We are in a diverse area with fewer reeds, and rather high thick-stalked grass with islands of trees and the odd palm tree here and there. We have worked our way towards a herd of buffalo but cannot make out a decent bull. I decide to get a bit closer to the herd to have a better look. The buffalo slowly move past me, more and more of them appearing out of the high grass. I can see only young bulls and soon the first buffalo have almost gone around me; they get my wind and the whole herd stampedes away in a huge cloud of dust.

It is still early and we continue our stalk in an easterly direction. On one of the islands, I climb a tree to look ahead. In some distance behind the next island, I spot some buffalo and we decide to take a look at them. On our way through a field of about hip-high grass, something suddenly jumps up in front of us. Through the binoculars, I see that it is a serval – what a rare sighting! I try to snatch a photo of the elusive predator but he has already disappeared in the grass.

We stalk on and eventually can make an excellent approach to the buffalo herd, using a shallow gully for cover. We are quite close to the herd in a patch of reeds, while the buffalo are on the edge of the reeds. It is a mixed herd with one bull that may be old enough, but we cannot get any closer unnoticed and therefore decide to leave them in peace.

The afternoon sees us at the muddy pond again. As we come around the bend I get up on the riverbank to look into the depression where the hippo was the day before and immediately see the back line of a buffalo. Through the binoculars, I can make out its hairless, scraggy back and shoulders – without even seeing the rest of the animal I know that this is an old bull!

We immediately get into a shooting position; the bull is still down in the pond and we have to wait for him to get out. After a while he turns around and we can now see the top of his head – he has a most impressive set of horns above his hairless, scarred face – this is a truly ancient bull. The horns are short, with blunt worn tips; the boss has large chunks broken out and is worn smooth as can be – what a buffalo!

At this moment another bull appears out of the pond and moves onto ‘our’ side, where he stops for a short moment and looks in our direction. It is also an old bull with a magnificently long right horn and incredibly broad boss. The left horn is broken off with only the boss remaining. He makes his way onto the opposite riverbank and then disappears in the reeds. We let him pass, as Uwe would like to bag a bull with even horns. The ancient bull also gets going now but does not follow the other bull, instead, moving directly into the reeds without presenting the chance for a shot. I know that buffalo bulls like these will only come along a few times in life, especially together like these two, and therefore Wanjo and one of the game guards move into the reeds on the other side of the river to try and push out the two bulls. They, however, know this game and disappear deeper into the reeds. I am truly shaken by these two bulls and just hope that we will find them again.

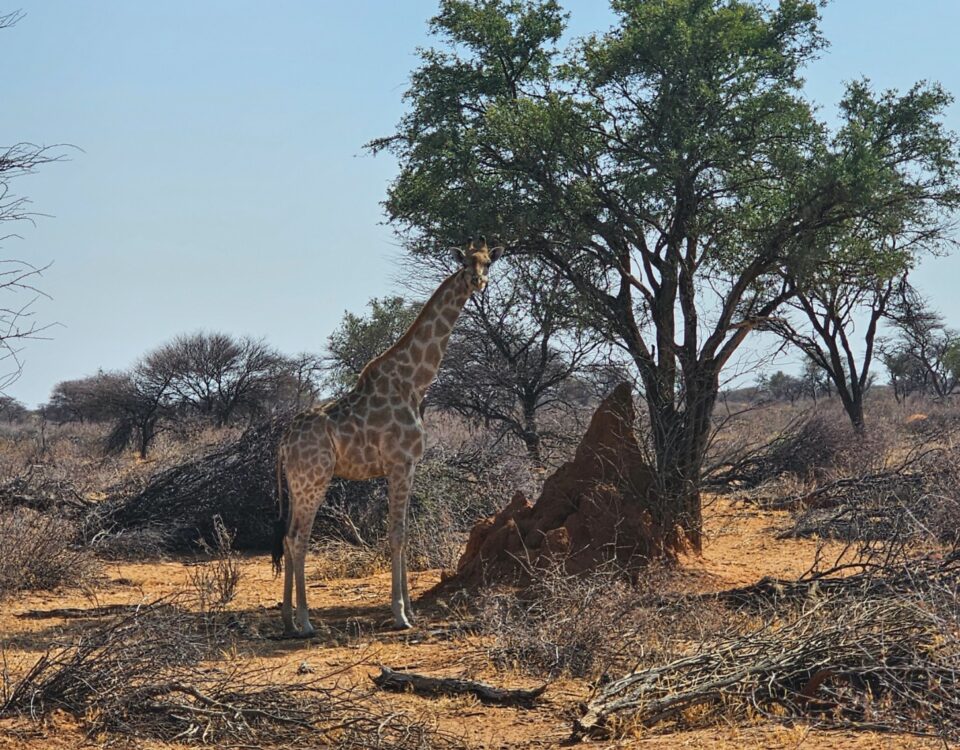

We are stalking along the sidearm the following afternoon in search of the two bulls. As we get closer to the dry Linyanti River, the sidearm fans out and becomes relatively flat. We stay on the northern riverbank, stopping here and there to glass ahead. Suddenly we hear a reed cracking in a patch of thick reeds some eighty yards from us in the wide riverbed. We stop to listen, and the cracking repeats every few minutes. The trackers are sure that this must be a buffalo, most likely a single bull. We move into the cover of a termite hill and wait for the buffalo to appear. For ten or fifteen minutes we just hear the occasional cracking of reeds. I decide to get up onto the termite hill and hopefully have a better view. Not before long the head and shoulders of a male lion appear out of nowhere in the reeds.

I am completely taken aback by this as I was expecting a buffalo, and quickly make the others aware of the lion. We had seen lion tracks before, but I would not have expected to see a lion, especially not this close. The lion stares intensely at us and a strangely uncomfortable feeling spreads in my body.

Encountering a truly wild lion in such wilderness is always an incredible experience; after taking a few photos we decide to make our way back along the river.

The game guard walking at the back suddenly stops us as he has seen a few buffalo in the distance, coming out of the dry open forest in Botswana. I can see three or four bulls just disappearing into the reeds framing the Linyanti. We quickly make our way along the sidearm past the muddy pond; the buffalo will pass the sidearm further to the east. As we hurry past a steep part of the riverbank I hear a hissing sound coming from the bottom of the bank. The bank has a slight overhang with the roots of the reeds hanging just above the ground. Behind this natural curtain, we can make out the contour of a small crocodile, which upon our approach disappears in a narrow cave behind the root curtain – incredible how this prehistoric reptile has decided to try and wait out the drought until the floods return, probably snatching a bird or small mammal every now and then.

On we walk in the river to cut off the buffalo bulls. The river makes a sudden sharp bend to the right and sixty yards onwards we find a second muddy pond, this one holding more water than the other one.

I reckon that the best chance of seeing the bulls is if they come to this pond and we, therefore, decide to wait here in cover. The sun is setting quickly and, other than birds, nothing appears at the water. The buffalo have either gone another way or will only come to the water at night and we have no option but to try again the next day.

Like the afternoons before we head to the side arm of the Linyati that still has some water ponds in it. One of the game guards and a tracker check and wait near the second pond, while we stalk to the other one. We haven’t really settled in yet when I hear whistling from the direction of the second pond. Looking over to where the whistling is coming from, I can see the tracker excitedly waving and gesticulating. We immediately get up again and quickly move over to the game guard and tracker, who have indeed seen a buffalo.

The pond is around the next bend of the sidearm and I decide to first take a look around the “corner” and see what the bull looks like. The buffalo is standing above the water on the riverbank on the fringe of a reed thicket. It is, however, a young bull. I intensely glass into the reeds in the hope of spotting another bull in there somewhere, but cannot see anything. Due to the course of the river, we are on the same side of the river as the young bull. To the left and in front of us there is a clearing free of reeds, all on the opposite riverbank. The dry riverbed bends around the clearing to the left and then disappears in the reeds to the northeast.

I glance back to the young bull and immediately notice a movement at the bottom of my view field in the binoculars – the shoulder line of another buffalo! He is down in the pond – which I realise now is on a much lower level from our position than the rest of the riverbed. Although I cannot see much of the buffalo, he seems more mature as his back appears to have less hair, yet I cannot really size him up.

He doesn’t move much for a while, so I first retrace my steps back to Uwe and let him know what I have seen. I suggest that we move across the riverbed, using the bend of the river as cover to get to the opposite riverbank.

Uwe, Wanjo, game guard Niklas and I stalk through the dry riverbed, while Uwe’s wife and the rest of the team stay behind in the cover of the reeds. The bank of the river is some six feet above the riverbed and my hope is that we may be able to get a shot over the edge of the bank when the bull moves across the clearing – if he does. As we reach the bank, I indicate to the others to crouch down behind the bank, while I peek over and see whether the bull has moved. As I look over the edge, the buffalo moves across the river towards our side of the river – it is a good mature bull. He is still in the riverbed – which is higher on the other side of the bend – but is coming towards us at an angle, which will bring him within fifty or so yards of us. We must be extra careful when getting into a shooting position over the bank’s edge.

We have to take a few steps along the river so that we can walk up the bank and position the shooting sticks. Time is of the essence and we quickly get into position, still crouched in cover. Wanjo sets up the shooting sticks and we get Uwe behind the rifle to get ready. As we rise above the edge, the old bull is coming out of the riverbed onto the clearing; he must have noticed a movement because he stops dead still and glares over to us from underneath his boss – these are intense moments as we may not move and cannot shoot, with the buffalo still at an angle towards us.

The young bull is already across the clearing and there is another bull ninety yards behind the old one, beyond the river. I am standing slightly behind Uwe to the right, rifle at the half-ready. Nobody dares to move, while I whisper to Uwe to wait until the buffalo relaxes – hopefully – and take a shot when he is broadside. After a few long moments, the bull lowers his head, takes a step forward, and presents his complete broadside.

Uwe does not hesitate and lets it fly. The buffalo shows no reaction to the shot and takes off. As I am not sure where the bull is hit, I immediately put a round into the running buffalo. He is aiming for a thick patch of reeds – I am not going to let him get away, run in a semicircle after him to get a better view and put myself in danger of bullets from behind. The bull disappears in the reeds but luckily reappears on a small reed-free patch where he acquits my next shot onto his spine, breaking into the reeds to his right. We hear a few stalks cracking, followed by dead silence – and then the moaning death- bellow brings an end to the hunt. We wait for a while, nervous laughter and relief filling the cool evening air as the tension ebbs off.

As I walk back to fetch the hunting vehicle, I for the first time in days can truly stride out and freely breathe the fresh air. We have brought this hunt to a satisfying and safe end – something one can never be too sure of when hunting dangerous game. Uwe has been able to fulfil his dream to hunt for a good buffalo and what remains are the good memories in one of the few spots remaining in the Zambezi Region that gives a feeling of wilderness. As we pull up to the camp later that evening, the trackers and game scouts are singing of a successful hunt on the back of the pickup, Goosebumps run down my spine as I am reminded of how natural and raw this life can be.

I drift off to sleep, looking forward to coming here again and hunting buffalo, maybe someday bagging a bull myself – an old bull like the ones we saw on that third day.

Although the contract runs out this year, Felix is confident that he can renew it, as he maintained good relations with the local community.

Three months later Felix tells me that the conservancy committee had a change of mind and the concession is likely to go to a businessman.

Later I hear that seemingly the traditional leader, out of protest, apparently has started planting crops again and soon, when the river is in flood again, fishermen will probably also return. With that, the dreams of young hunters have come to an abrupt end.

What remains then are memories.

This article was first published in HuntiNamibia 2018.