African buffalo: The Able-Bodied Warrior of the African Savannas – An endlessly fascinating game animal

January 9, 2019

Eventful days at the Linyanti

January 9, 2019As always, we were welcomed by hundreds of Yellow-billed Kites hovering over the town, and by our laidback PH, Dawid, who on the way to his hunting concession also pointed out the severe effects of the lingering drought on the local communities. However, these sad impressions soon gave way to the welcoming smiles of Dawid’s camp staff, the familiar calls of Arrow-marked Babblers around the lapa and the aromas of lunch drifting towards us from the kitchen as we arrived at his hunting lodge, nestled among riverine vegetation and overlooking a slowly whirling side-channel of the Kwando River.

A brief indaba with Dawid and his game scouts and trackers revealed that the extremely dry conditions also had an impact on the movement of buffalo and elephant in the area and that hard work lay ahead in the coming week. Not only the boundaries of the vast and completely unfenced concession area but also the long-known hideaways and crossing channels of buffalo and elephant on and between the various islands would have to be scanned daily at dawn and at dusk to detect any movement of individuals or herds of buffalo and elephant. When we retired to our reed bungalow after lunch for a siesta in the sweltering early November heat, it was evident that the next few days would be no mean feat.

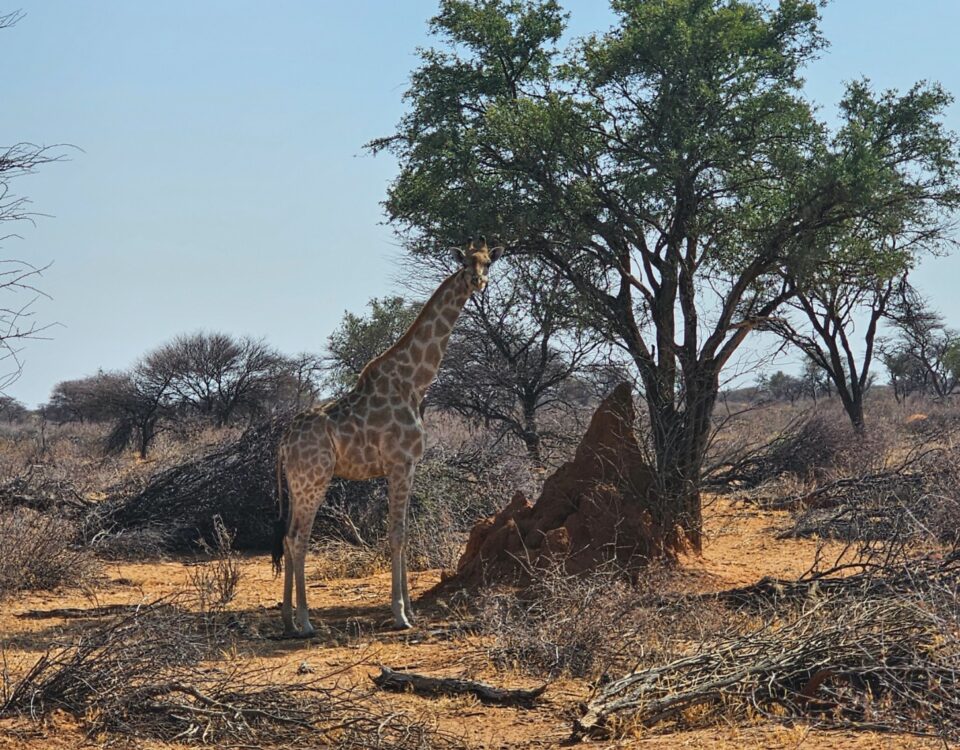

While our daily patrols through the concession area revealed no buffalo and only small breeding herds of elephant, we encountered amid occasional veld fires, an amazing variety of predators and plains game – lion, leopard, hyena, black-backed jackal, roan, Chapman’s zebra, kudu, blue wildebeest, waterbuck, lechwe, impala, bushbuck, duiker and steenbok.

In addition, the regular sightings of Fish Eagles, Tawny Eagles, Verreaux’s Eagle-owls, Lanner Falcons, Saddle-billed Storks, Spur-winged, Egyptian and Pigmy geese, Knob-billed, Fulvous and White-faced duck, Red-billed and Swainson’s spurfowl as well as Coqui and Crested francolin brought

a welcome variation to our otherwise monotonous patrolling of the concession area. These sightings provided wonderful food for thought and conversation as we gathered around the campfire towards evening to relax and enjoy the marvellous sunsets of the region.

Our hopes for an elephant bull flared up on only one occasion in the course of the week. Tracks of a breeding herd of elephant crossed our own in the loose white sandy soil of the Mopani forest to the north and among the tracks of cows and calves were those of a much bigger elephant – a bull? With the sun mercilessly beaming down and amidst the tremendous silence of the African bush in mid-morning, we started following the tracks in the hope of locating the herd somewhere in the dense thornveld. However, upon catching up with them, the big tracks turned out to be those of a huge tuskless cow, towering above the rest of the herd and glaring down at us almost contemptuously.

After another sweaty and restless night, our last day had arrived. Once again we were awakened by the generator throbbing far way and had coffee and rusks in the lapa at the crack of dawn while listening to the flute-like calls of White-browed Robin-chats piercing the morning air. Yet again our early morning patrol yielded no fresh signs of buffalo or elephant movement and on top of that, we ran out of fuel on our way back to the lodge for brunch. It was while waiting for assistance to arrive that Dawid’s chief game scout called. He had just located three dugga boys along one of the side-channels of the Kwando River and asked us to come immediately. With brunch forgotten, adrenalin rushing through our veins and sweat streaming from our bodies, we set off over the now mostly dry floodplains scattered with deep tracks of elephant, buffalo and hippo, and along the way through some of the smaller side- channels of the Kwando River.

Upon wading through one of these channels, Rian’s and my eyes met in the exhilaration for a moment, as Dawid’s command to chamber a solid and put our rifles on safe coincided with the exuberant and ringing call of an African Fish Eagle.

It wasn’t long before we caught up with Dawid’s game scout, Hendrik, who enthusiastically urged us to crouch as we started following his lead.

Hendrik stealthily guided us through increasingly dense vegetation and up to a knob-thorn tree from where Dawid and Rian commenced their final stalk towards the dugga boys, restlessly moving around behind a clump of bird plums a mere hundred metres ahead of us.

A full hour ticked away before we almost unexpectedly heard the crack of Rian’s .375 H&H, followed by the deeper report of Dawid’s .470 NE.

With warblers, weavers and little White Egrets exploding from the reeds, the dugga boys took off along the side-channel. They scattered, but it was evident that one of them was hit, as it soon dropped behind and took refuge in a clump of dense undergrowth. Its death bellow amid the deafening sounds of cicadas and the alarm calls of a number of Go-away Birds brought some relief and confirmation but still required an extremely cautious follow-up into the thicket. However, with nothing more than an insurance shot required, we could join in the exuberance of Dawid’s guides and trackers, as with a deep feeling of reverence we kneeled next to the fallen dugga boy.

Amid swirling flocks of weavers returning to the reeds along the channel, Rian and I were on our way back to the lodge feeling a quiet gratitude towards Dawid for a truly African experience through which we could also make a contribution to the Namibian Game Products Trust Fund and to the livelihood of the local community.

With the recent ban on hunting on state land in Botswana and the gradual deterioration of hunting opportunities in many other parts of Africa, due to poaching, corruption, illegal wildlife trade, commercialisation, terrorism and other factors, Namibia has indeed become a hunting destination of choice for many from all over the world.

This sentiment is to be understood against the background of a number of important factors.

Namibia is not only the youngest and arguably the most peaceful country in Africa, but with a population of only 2.3 million, it has the lowest density of people per square kilometre on the continent.

The country’s 13 regions extend from the Namib and Kalahari deserts in the south and the vast savannah landscapes in the centre to the lush areas bordering on the Okavango and Zambezi rivers in the north. Its flora and fauna include 14 vegetation zones and 200 endemic plant species, the Big Five, 200 mammal and 676 bird species – a combination that creates an almost irresistible attraction to tourists, photographers and hunters.

The protection of this splendid natural environment is enshrined in Article 95 (1) of the Namibian Constitution and is reflected in respectively 46% and 17% of the country’s 824 268 square kilometre surface area being dedicated to some form of conservation management and to National Parks that also include the country’s 1 570 km of coastline.

Within this context, hunting in Namibia is strictly regulated and largely free of corruption and the abuse of wildlife. No hunting is allowed on land smaller than 1 000 hectares, and in practice, hunting occurs on much larger and often vast areas of unfenced land. Furthermore, hunters generally regard Namibia as a ‘rifle friendly’ country since only the importation of pistols, revolvers and automatic or semi-automatic weapons is prohibited. Also of great importance is the fact that hunting in Namibia is firmly connected to the country’s very successful Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) initiative through which an important link between conservation and the development of rural communities has been established.

It is through this initiative that rural communities annually derive direct income from selling hunting opportunities to hunters and that my brother, Rian and I, recently again had the opportunity to follow the spoor of buffalo and elephant in the Zambezi Region of Namibia. This time our permits allowed for two buffalo bulls and an elephant bull that, apart from making a substantial contribution to the Namibian Game Products Trust Fund, would also provide us with a truly African experience!

This article was first published in HuntiNamibia 2018.