Gemsbok: Hunting Namibia’s Most Formidable Swordsman

January 11, 2019

A place for Lions

January 11, 2019The farm covered an area of 19,000 hectares, roughly forming a triangle with a side length of 20 km, and quite a varied landscape: vast grassy plains where springbok and ostriches roamed, zebra country with gently rolling hills which reminded me of the hills of Exmoor where a long time ago I used to gallop across the moor at breakneck speed, following the pack, chasing the fleeing stag – that Exmoor, stronghold of my soul, which I loved so much and where never again the bright chimes of a pack in full cry will ring out; so, same hills here, but rocky and parched. I baptised this area of the farm Little Exmoor. And then, incised by deep ravines, the uplands of leopards, klipspringers and dassies (rock hyrax), and finally in the low mountain range in the northeast the gemsbok country, which consisted of the Swakop River’s badlands.

It was late in the year, shortly before the end of the hunting season, and the vegetation was sparse. The yellow withered grass stood calf-high, and only the evergreens among the few bushes and trees, like the Boscia species, still sported leaves. But there are incredible survival artists in this desert landscape: numerous magnificent specimens of aloes, the quiver tree, graced the slopes and their branches and leaves were silhouetted against the deep blue sky like fans in front of velvet blue wallpaper. The blue-leaved corkwood with its richly toned bronze- brown bark peeling in the typical papery strips and akes, for which it is also called a paper tree, pushed through everywhere from the rocky soil and grew in the ravines, sometimes from the tiniest rock crevices and on exposed ledges, as if it had no roots at all, as if it were just glued to the bare rock.

In the valleys of seasonal rivers with subterranean water grew the lush green toothbrush bush, which Namibians call lion bush or mustard bush. Since time immemorial the twigs have been used for oral hygiene by various peoples. First, you chew on one end of a twig until it is frayed and then you apply it to your teeth as if it were a brush.

The fibrous twigs contain tiny crystals which have a gentle abrasive effect. It also has anti-microbial substances and the high fluoride content hardens the tooth enamel. Thus a twig is a toothbrush complete with toothpaste, called siwak or miswak. Found from Africa to India, it was used for dental care already 7000 years ago by the Babylonians and later also in the empires of the Egyptians, Greeks, Romans and Islam. According to a study, a siwak cleans better than a modern manual toothbrush.

It was not unusual to also find in the seasonal rivers a kind of tree with extremely hard and heavy wood: the lead-wood tree. Since this wood produces very hot and long-lasting coals, we always gathered the dead branches for our campfire on which we cooked our meals and which provided warmth in the mornings and evenings. In the Herero and Owambo culture, this tree is seen as the progenitor of all animals and people, which is why it is also called the ancestor tree.

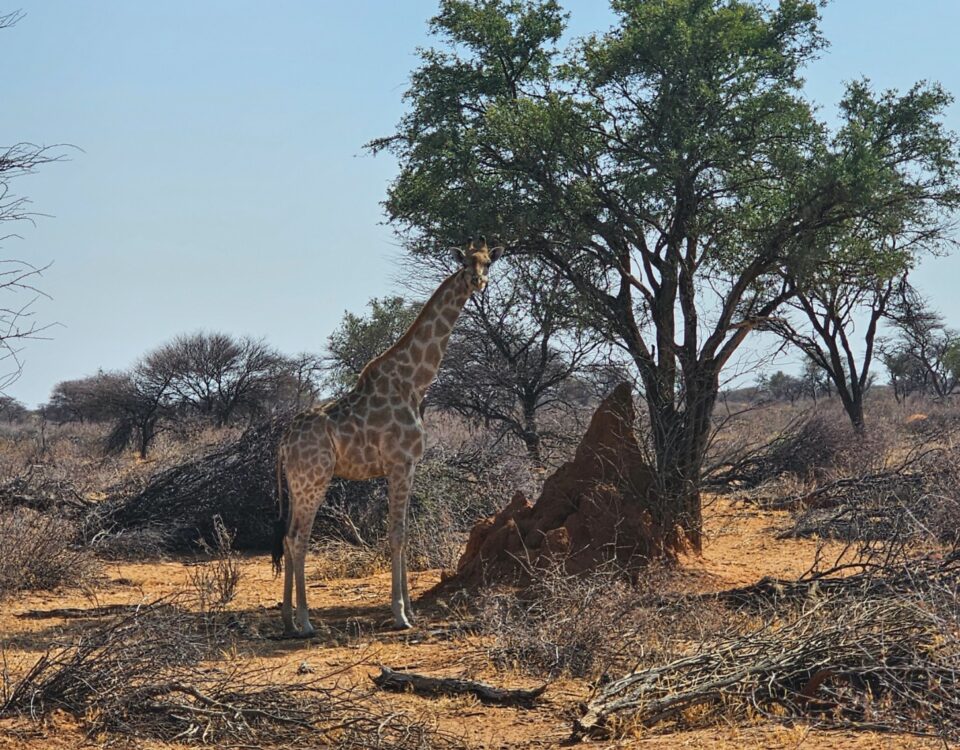

A widespread acacia species is the camel thorn. Giraffes love its flowers and use their long tongues to pick them skilfully from between the large and pointed thorns. The sickle-shaped, hairy pods are eaten by many wildlife species. During the dry season, the Ana tree provides game animals with large, nutritious pods.

Of course, many succulents are also found in the desert. Here, in the Rooi Kuiseb area, the most common was poison bush, a large spurge plant resembling a cactus, which grew especially on the bare mountain slopes. San hunters use the highly toxic milk to poison their arrows. Euphorbias seem like green octopuses reaching upward with their thorny arms, but when they die they look like a miserable little heap of greyish black steel wool as if an evil witch had withered into a skeleton of spines.

What we saw on our first exploratory trip through the area, in addition to all of the above plants, were gemsbok, mountain zebra, klipspringer and dassies, which seemed to slide across the steep rock faces like a swarm of shooting stars in the night sky. When we approached they scurried just as quickly over the smooth rock and disappeared in holes and niches as if they had never existed.

We, Hartwig von Seydlitz, Bippas the trackers, Muvi the cook and me, pitched our camp on the edge of a ravine in the vicinity of a borehole. The water was very brackish, but at least there was water. Good drinking water is extremely rare in this area.

On one of the following days, after I had already bagged a big female gemsbok, we set off for an extensive stalk in the hills between the two branches of the Rooi Kuiseb close to the so-called Baboon Post. We came across a small herd of young Springbok, saw gemsbok on their way in the distance and repeatedly heard the distinctive, frog-like call of Rüppell’s Bustard, the well-footed one, or the high-pitched delicate voice of the Namaqua Sandgrouse. At noon we checked our bait, which we put up the day before and found dozens of gemsbok and mountain zebra at the waterhole. Days before we had happened upon a leopard kill: a zebra foal that was mortally wounded but still alive. I put it out of its misery and we left it as bait, not with the intention to shoot the leopard but as an opportunity to possibly observe it. Unfortunately, the leopard did not return. Perhaps he even had perished as a result of being kicked by a zebra or perhaps he was badly injured, otherwise, he would not have left the foal just like that.

After feasting on the gemsbok’s heart, liver, kidneys and intestines the previous evening, we now had a very special delicacy for lunch: boiled udder with sweet potatoes in a tasty, creamy sauce. What can be more delightful than enjoying skilfully prepared culinary rarities?

Siesta in the tent. It was hot. Even the strong gusts of wind blowing through the large insect screens were a fiery breath of heat. Yes, it was really hot, wonderfully hot. And I was happy. Because I find nothing more dislikeable than the cold.

Only at five in the afternoon – at this time of the year the sun drops at a quarter past seven – we passed through the main mountains to the Rooi Kuiseb and from there to the southern plains to look for springbok. Far in the west, we saw a group of seven taking flight. We drove on to get an idea of the land. But game was nowhere to be seen. All of Little Exmoor and the vast plains were deserted. Finally, we returned to the area where we had previously spotted the herd and began to stalk. First, we climbed a small rock formation and scanned the sprawling, gently undulating terrain below with our binoculars. The small herd now stood half a mile away, to the north. The wind was favourable and, covered by a tallish hill, we worked our way forward. The springbok were grazing on the opposite slope, moving over the hill. We followed. But when we reached the ridge we saw the herd even further away in the next valley. We could have moved on, to a rocky crag rising to the left, but dusk was already setting in. And with open sights, one is much more limited than with a scope. So we enjoyed the view for a while and then retraced our steps.

The dawn rose over the mountains again. As soon as the day becomes brighter, crickets start to rev their engines. One of them sat right above my tent. First, it had to turn the ignition a couple of times before it got the engine going. Zzz… Zzzzz… Zzzzzzz. Once it was running the cricket stepped on the accelerator and steadily increased its speed: one thousand hertz, three thousand, five thousand, seven thousand, nine thousand… it is nerve-racking. You simply have to turn over in bed and forcefully keep yourself from listening. But in any case, Muvi already brought a jug of hot water and set it down on the table in front of the tent. Instead of limiting my morning wash to brushing my teeth, as I do on freezing winter mornings in the desert, I enjoyed the pleasant warmth and took time for washing properly.

After breakfast, we repeated our walk in the mountains at Baboon Post. In the afternoon we sat on watch right there before we started the long march back to camp. It had been overcast all day, with dark clouds gathering in the east. Every now and then there were flashes of lightning in the distance, and the deep rumble of thunder heralded rain. But it was only a few drops. Just a faint shower for several minutes.

The next day Hartwig sounded the reveille an hour before sunrise. We wanted to set off early and drive to Little Exmoor to scan the plains with our binoculars. But only dead silence everywhere. Around eight we randomly started to stalk through the flat hills west of Little Exmoor, close to where we had spotted the small springbok herd two days earlier. We passed a rock cave from prehistoric times, in which we found an old grinding stone, and then continued to walk from hill to hill, always against the wind, until we happened to come across the faded skull of a springbok with extremely good horns. I picked it up, took it with me and while I still mused over it I almost bumped into Hartwig and Bippas who suddenly stood there as if rooted to the spot: our little herd was grazing in the shallow depression in front of us – a mature ram with two young males and five females.

Cautiously, we withdrew and walked around the hill to get closer. Again we saw them, but in the meantime, they had moved on and were still too far away. Another detour, longer than the first one. When we peeped over the next crest the herd stood in a sloping depression, but again it was damn far away. The springbok had also noticed us and doubtfully tested the wind. We had to act. In anticipation of a long shot, I had shifted the visor a notch higher before we rounded the hill, and that was to pay off now.

Hartwig positioned the shooting sticks, and I took aim. At first, the ram stood looking towards us, his head just a white dot which I barely recognised with the iron sights. When at last he turned, a female pushed past. But finally, he was clear and stood broadside, seeming larger to me now, with his contours clearly visible. The sights were trained at his shoulder, or at least they more or less rested there. Then they had found their aim. My finger knew how to deal with that four-kilogram trigger. The shot rang out and the springbok collapsed.

“Keep aiming”, Hartwig called while I reloaded, “he might get up again”. But with the spine severed by a high shoulder shot the springbok stayed down.

Hartwig asked for my Geovid and measured the distance: “234 metres, fantastic, well done!” he exclaimed and slapped me on the back.

Inside, however, I felt ashamed that Lady Luck had favoured me like that. It was ten o’clock. After two days of cloudy skies, we had glorious sunshine again, just in time to take a few pictures.

For a few minutes, the pronk of a springbok stays open, then collapses.

The author with PH Hartwig von Seydlitz at one of the rare natural springs of the area.

My philosophy had been confirmed once again: in order to hunt well, to really go hunting, you don’t need any high-tech.

But if Hartwig would have told me before that it would be a shot of more than two hundred metres, I would have given him the thumbs down. In spite of all my good luck: with open sights, this no longer conforms to the principles of sportsmanship. Nevertheless, I was pleased beyond all measure.

We spent the rest of the day with a trip to a remote part of Rooi Kuiseb, where an elongated nameless ravine with bizarre rock formations and sparse vegetation cuts through the mountains. It was only accessible from neighbouring properties.

In the evening a chilly, almost cold westerly wind blew in from the sea so that you had to put on a jacket, and at night I snuggled up in my sleeping bag. Temperatures are so variable in the desert! At midday forty-five degrees in the sun, on a windy night maybe seventeen. Desert is always extreme. I am still lost for the words that would do justice to the surreal beauty of this landscape, its grandeur, its sublimity, the vast expanse, the hills, mountains, canyons and rock towers, the light, the colours, the flat glistening harshness of noon, the deep powerful reds of the evening, the soft pastels of the morning, the whole rough sparseness in all its diversity.

For supper, there had been all sorts of springbok delicacies: the testicles as amuse-bouche, followed by heart, liver and kidneys. For the next day Muvi prepared the rumen with great care, and indeed it turned into superb tripe in a tasty sauce. Our field kitchen, by the way, became a meeting place for very special guests: numerous scorpions sought shelter among the large boxes. But such trifles definitely wouldn’t ruin my appetite!

When the others turned in that evening I remained outside for another quarter of an hour and savoured the silence. I looked at the infinite dome above me with its unfathomable number of stars shining brightly from the night sky, unaffected by the lights of cities and villages, unclouded by polluted air. The Milky Way and Scorpio were high above, the Southern Cross was on the horizon, but the darkness of the nights decreased constantly because the moon was waxing and finally its light was so brilliant that it spread a silver veil across the land.

Translated from: C. C. Willinger (2013): Good Sport & Fair Chase – Weidwerk im Geiste ritterlicher Jagdkultur

C. C. Willinger (work in progress): Durch Wüste und Savanne – Ursprüngliches Jagen zwischen Namib und Sambesi

Published in 2018 by the same author: Auf Leben und Tod – Ein Kulturjagdreisebuch

For a few minutes, the pronk of a springbok stays open, then collapses.

This article was first published in HuntiNamibia 2018.