How I learnt to love the Desert

January 11, 2019

Torra Conservancy: Lion Hunt in the rugged northwest

January 12, 2019It was a time when there were still many lions in the Namib at the lower course of the Omaruru River. Old maps show an Omaruru River Game Reserve there. In the riverbed in the middle of that former reserve is a spring which does not even dry up in years of drought. In years of good rains, a small stream of wonderful water seeps through the sand below the spring for a distance of several kilometres, sustaining lush vegetation on the riverbanks. This area was lion country. Right into the 1970s lions occurred there permanently, and repeatedly made forays onto farms.

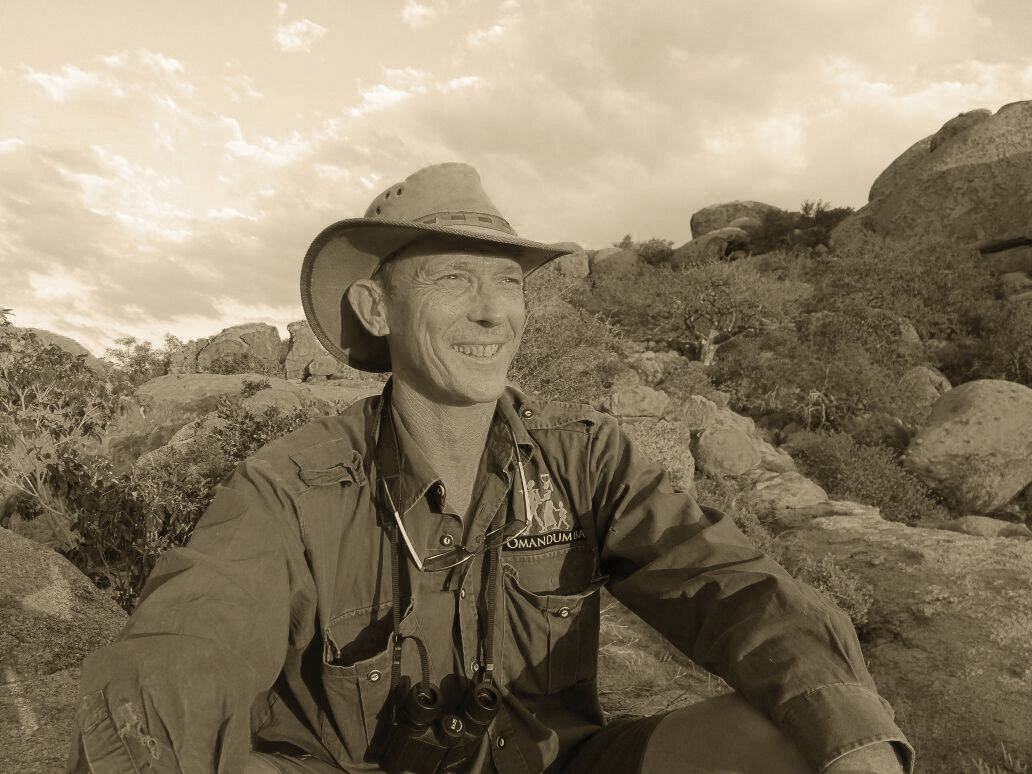

In 1968 a large male lion had been causing trouble on the farm Omandumba for weeks. He had already helped himself to twelve of my grandfather’s cattle. As a result of complaints to the Nature Conservation Department the famous game warden, Peter Stark was despatched from Etosha National Park. He tracked the cattle glutton on horseback. The lion slipped away into Damaraland, however. They simply couldn’t get hold of him. After three weeks of painstaking but unsuccessful pursuit, they gave up. The authorities then granted my grandfather, Godofred, permission to kill the lion. My grandfather was determined to bring the hunt to a successful conclusion. He took his .300 Savage without riflescope to the Hordabis Post (since then renamed Lion Post) to lie in wait at the top of the windmill. It was 14 feet high and pumped water from a depth of 12 metres. A seat was constructed up in the windmill and the torch mounted onto the weapon.

Nothing happened on the first evening. But already on the second evening, my grandfather heard an animal with a coarse tongue guzzling water down below. He trembled with excitement, got ready and turned on the torch. The beam of light revealed a leopard. Nothing else stirred at the drinking trough until morning.

Six days later the lion finally came to drink. It was September 29th, 1968. My grandfather had to force himself to calm down before firing a careful shot in the dark. When he was about to get off the windmill he suddenly became worried that the lion might still be alive and thus decided to rather stay up there until dawn. The next morning Godofred climbed down to the ground. There was no lion. So he called neighbouring farmers to help track him down. They followed the spoor with dogs, which on the granite wasn’t easy. Slowly they worked their way forward on the blood trail.

Now, my wife Deike and I are the third generation to manage farm Omandumba.

While they had a quick cigarette break they suddenly heard a shot. My grandfather had still been looking around and had spotted the wounded lion coming from behind a rock. The second and final shot was fatal. In fact, the lion had been lying in wait behind the rock heavily wounded. Tremendous relief.

Later my father, Ehrhart Rust, took over the farm. Livestock breeding was intensified everywhere and the lions disappeared from the lower course of the Omaruru River.

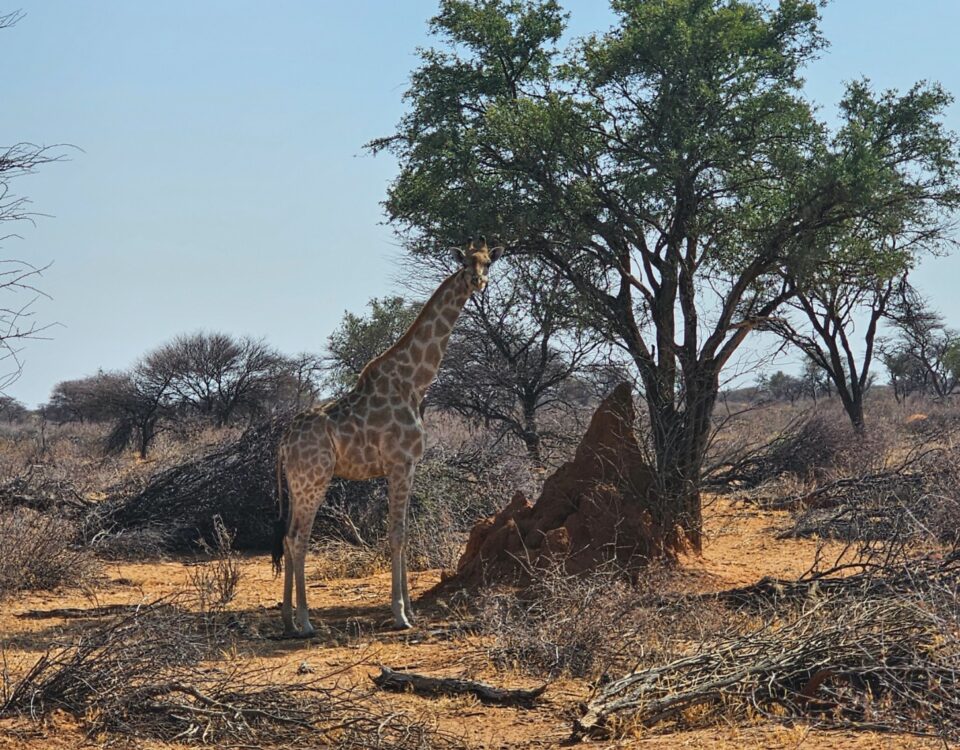

But keeping livestock in the sparsely vegetated, semi-desert mountainous terrain was not profitable. Tourism became an important alternative mainstay for farmers. My parents were founding members of the Erongo Mountain Nature Conservancy (now the Erongo Mountain Rhino Sanctuary Trust), which was initiated in 1998. Over the next years, black rhinos were brought back and the game populations recovered. Giraffe and black-faced impala were also reintroduced to the area.

In the years after the last lion was killed in the Erongo, from 1968 to 2017, Omandumba was used for breeding Karakul sheep, goats and cattle. Within half a century bush encroached all over the farm. Deike and I want to help restore nature to its original state, with everything that is part of it. That also means to once again provide a little more space for animals that may be poisonous, fierce or dangerous. Mother Nature did not intend that only harmless animals should exist. We want to be part of the whole picture and also give the lion a place to live again.

In 2017 the Ministry of Environment and Tourism approached the Erongo Mountain Rhino Sanctuary Trust with the request to give a home to four problem lions from Damaraland. The Trust agreed, which caused a lot of trouble with neighbouring farmers. But there is enough game in the Erongo Mountains. The lions are shy and have not caused any damage so far.

Every now and then their tracks are seen. It was a wonderful, exciting experience for us when we found lion tracks at Omandumba’s Lion Post fifty years after my grandfather, Godofred Rust, had shot the last lion there on September 29th, 1968.

This article was first published in HuntiNamibia 2019.