Danene van der Westhuyzen – NAPHA President 2018

November 20, 2018

Indigenous Species and their natural distribution in Namibia

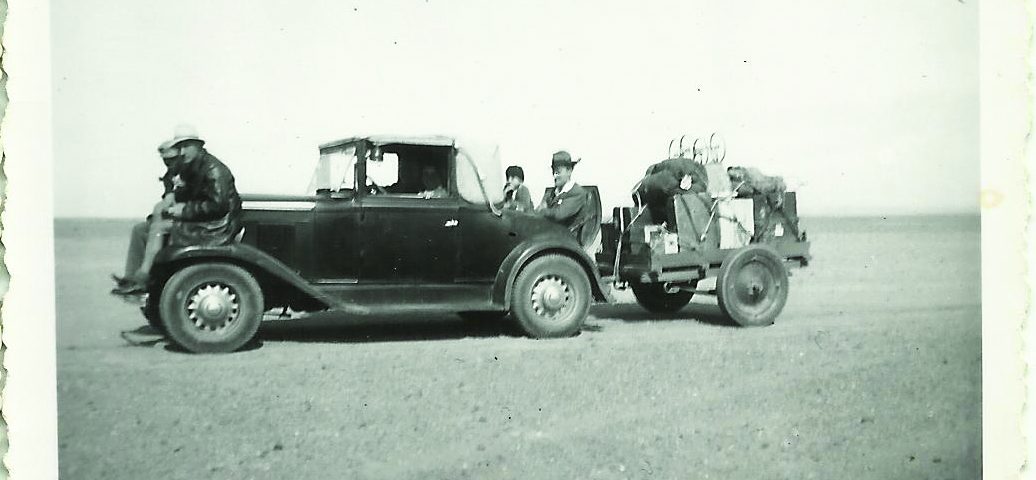

January 7, 2019T hen the visitor leaves the gravel road to, following a narrow track, cross two farms to eventually reach the border of the third – and last – of the farms on the western side of the C32, before the Namib-Naukluft Park begins. Only with difficulty one is able to decipher the inscription on a rusty and somewhat battered sheet metal plate at the entrance gate: Farm Wilsonfontein, Nr. 110.

Only a short while later one reaches the farmstead of what today is a hunting farm, in olden times founded at this spot close to the borderline of the huge property, because of a fountain, which by now has dried up. The visitor is as yet unaware of the grandiose landscape which opens up beyond; glancing over the surroundings he registers a downright charming simplicity and plainness amidst the wide horizons. In the backyard of the farmstead an old, time-expired Commer lorry – spadework, along with the hot desert wind, drifts into the face of the visitor, his curiosity aroused by now.

How might the owner of this place look like; perhaps one of those PH’s with a grim moustache, clad in camouflage, usual for the trade? Unlikely, for that the grass-thatched lapa, the extensive lawn, the pool is missing – all those things, which here would seem somewhat out of place and only would indicate a waste of water in these desert surroundings. Then one rather expects to see the wiry, weatherworn pioneering type with a sun-beaten face, wearing khaki shorts.

But then one is truly surprised.

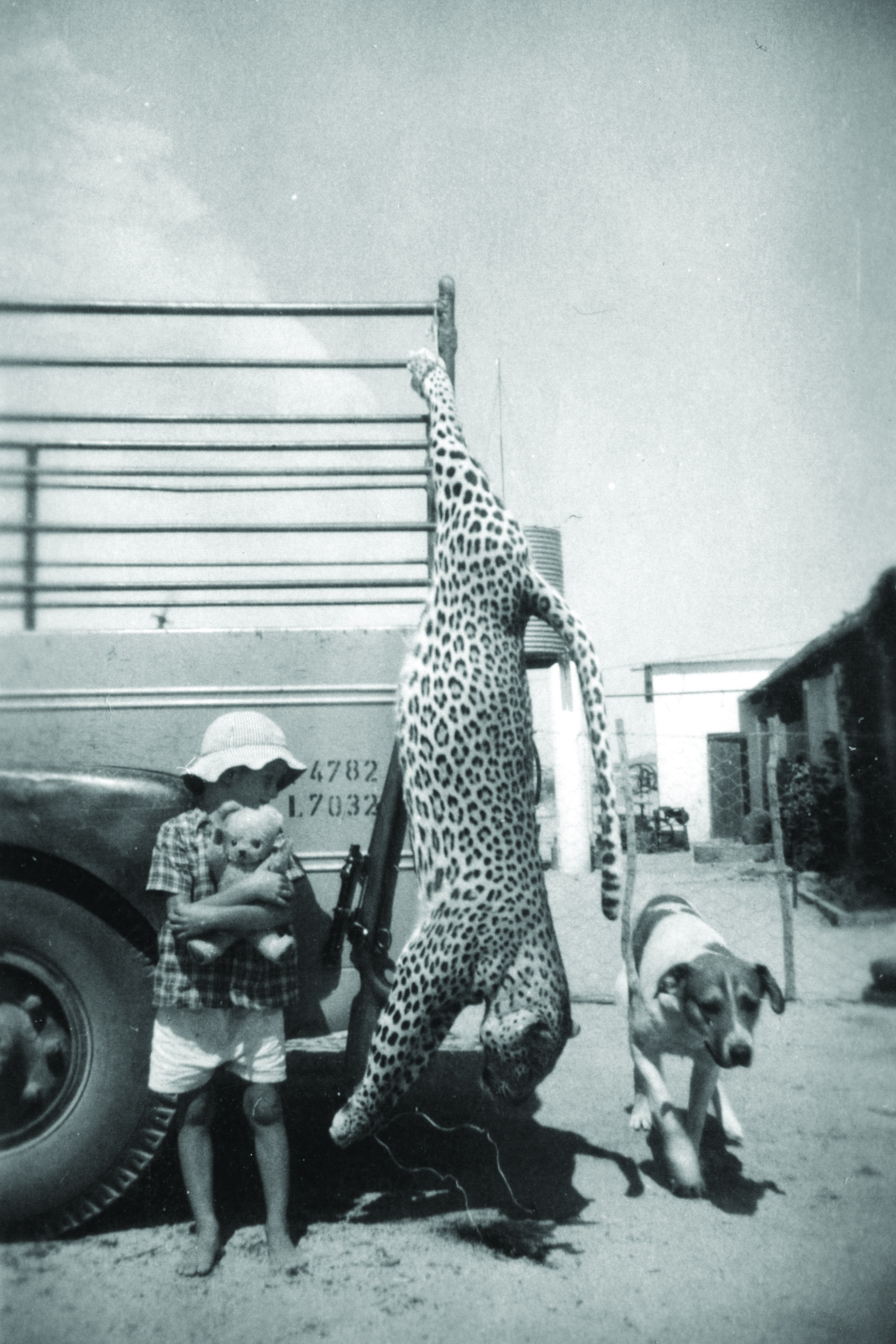

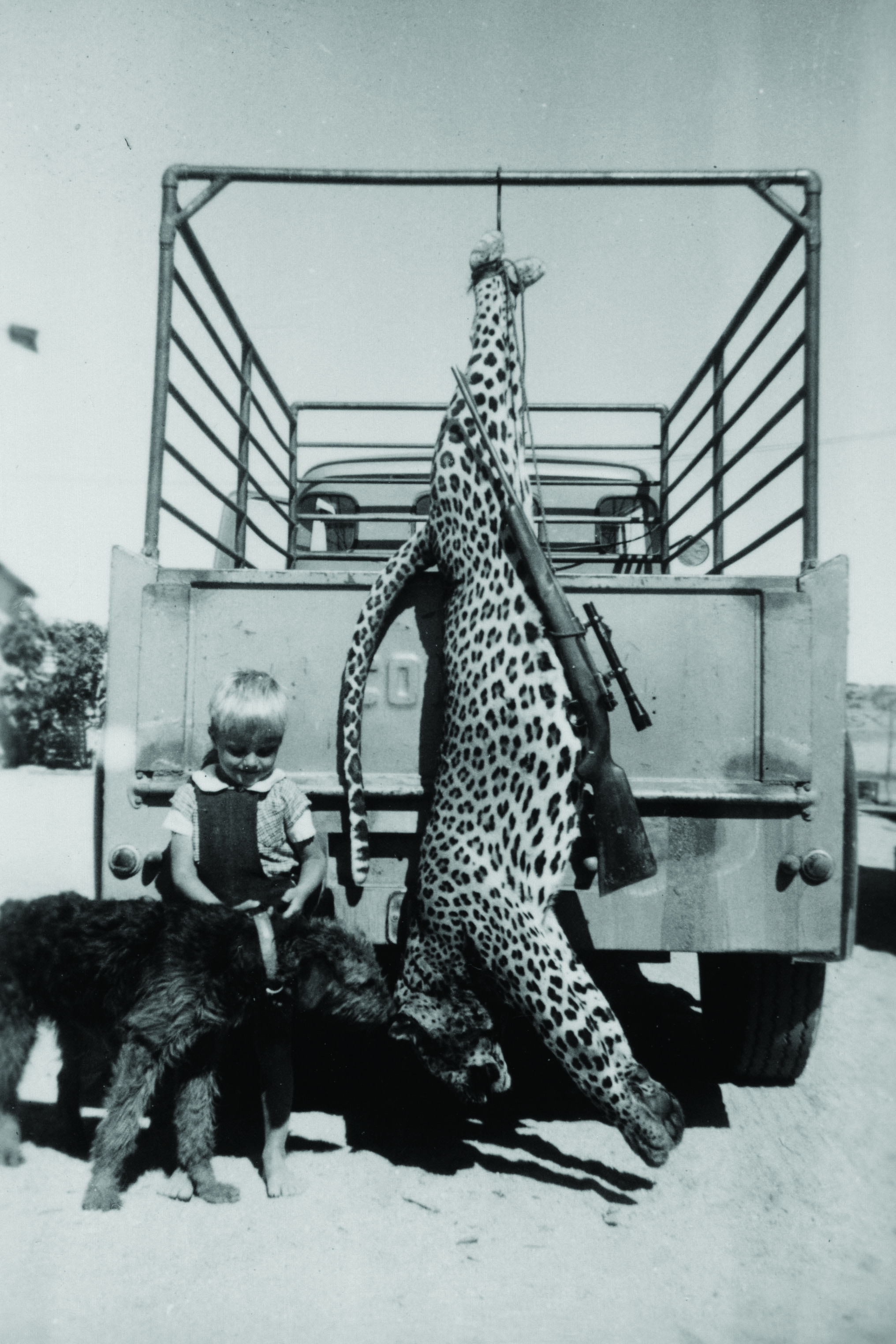

Wearing a white shirt, unbuttoned, but rather knotted up above the waistband, thus exposing a sleeveless brown vest and an amulet dangling on his chest from a thin leather string, in long grey trousers, the grey hair bound in a pony-tail, Ingo Gladis appears, the owner of Wilsonfontein. His glance is open and straight, his hands calloused and oil-daubed at the moment, the welcome hearty. When inside the plain farmhouse, amongst a number of photographs turned yellow over the years, an old picture catches the visitor’s eye, depicting exactly that old Commer lorry from whose railing a Mauser rifle, cal. 7×57, and a big leopard is dangling. Next to it blond little Ingo, perhaps five years old and the faithful watchdog, Nero, – this is as one learns – an old veteran, blind on both sides after fighting off a porcupine in the vegetable garden of the farm, the needle-sharp pins piercing his eyes.

The cool inside of the old house breathes subdued pioneering spirit just like the hot desert wind outside.

The photo dates back to the year 1956. The ancient Commer lorry, returning home from one of countless desert trips, breathed its last after more than a million miles and was pushed into retirement in the backyard – facing west where the landscape gradually drops towards the Namib Desert in grandiose uniqueness.

The farm was founded in 1938 by Ingo’s grandfather. Amidst unspeakable hardships, the early pioneers carved a living from this unforgiving desert country. Predators – lion, leopard, hyena – decimated the livestock on the farm in an intolerable way. In the year 1953, a pride of lions had killed 36 oxen within a few days, every year leopard accounted for more than 10 calves.

For this reason, Ingo’s father, Berthold Gladis, conducted a nightly drive twice a week, to keep predators in check. On the back of the lorry one of his workers, searching the mountain slopes and desert plains with a strong spotlight for the gleaming eyes of predators, on the seat next to Berthold his trusted Mauser rifle.

On that night-drive of 1956, when the Commer was jolting over stony terrain, the eyes of a huge cat were suddenly gleaming down on them from a rocky slope. Berthold brought the Commer to an abrupt halt and got ready. As soon as the crosshairs had steadied between the gleaming lights the shot thundered through the nightly silence. At first, blinded by the belching gun-flash, Berthold and his helper soon realised that the eyes had disappeared.

Was the leopard dead or was he just crouching behind a big rock?

They had to find out. Thus tying the spotlight – shining into the direction the cat had been – against the railing of the Commer with wire, Berthold and his helper climbed the slope with utmost care, rifle at the ready, to eventually find a big leopard with a tiny bullet-hole right between the eyes amongst the rocks, which they laboriously carried down into the valley.

In this way, Berthold Gladis shot 42 leopards during the years to keep livestock losses within bearable limits. Today livestock is no longer kept on Wilsonfontein and it is no longer necessary to destroy predators. In accordance with the principle of Sustainable Utilisation of Natural Resources, Wilsonfontein is now managed as a hunting farm. The circumspect, conservative way of hunting is much more environmentally friendly and pays due tribute to the grandiose natural setting.

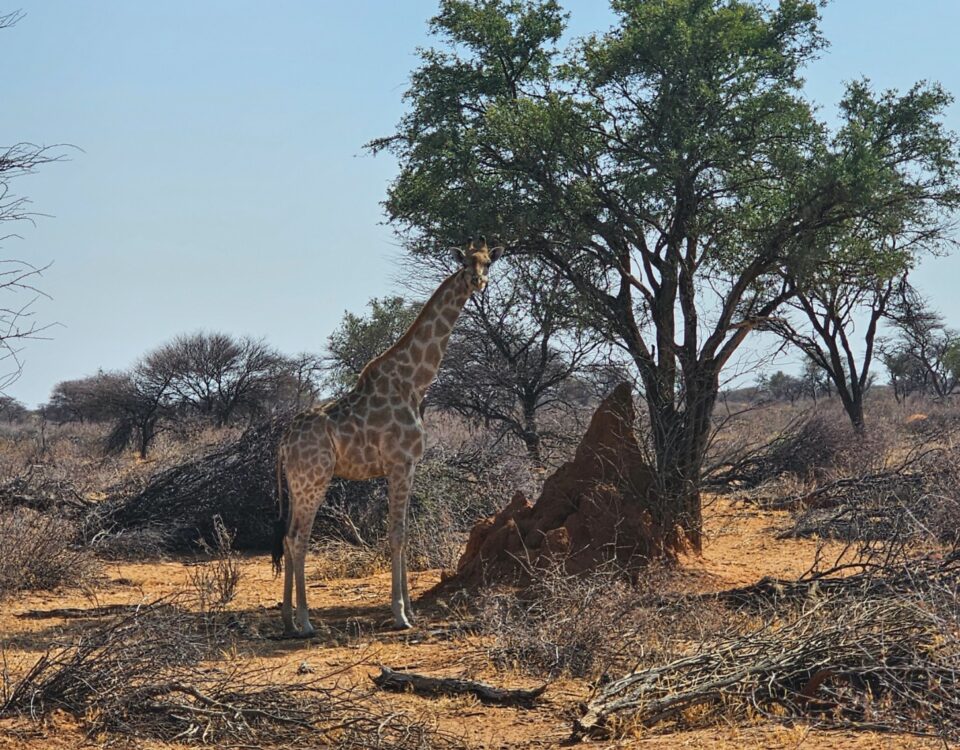

In the natural rhythm of good and bad rainy seasons desert game, at one time competitors in grazing for the livestock, – gemsbok, springbok and zebra – moves between the farm and the Namib-Naukluft Park and fills the wide plains and the rugged hillsides with marvellous life, while the predators fulfil their natural regulatory role. Even kudu and klipspringer live in the mountains. While on neighbouring cattle farms the campaign against the leopard continues, the sustainable hunt of gemsbok, springbok and zebra, as well as one old tom-leopard per year, helps to make one of the relatively few remaining original, authentic Namibian hunting farms profitable.

In the meantime, Ingo has cleaned his oil-daubed hands. He had picked up two clients in Windhoek in the morning, thereafter had to replace an oil-seal on his hunting car. Now the rifles are to be test-fired. Ingo steps up to the coffee table, where his clients, clad in spotless green hunting outfit from top to toe, have just enjoyed their afternoon coffee and says: “I don’t wear your begging-dress, but perhaps you still will come with me, we should test your rifles.”One has to grin and senses: this is exactly the kind of man, who, by virtue of his personality, is able to continue a third-generation tradition and counter the omnipresent total commercialisation and the superficiality coming with it; highly independent, upright – somewhat of an odd fish perhaps, but authentic.

It is to be hoped that the plain, lovable atmosphere will continue.

This story first appeared in the HuntiNamibia 2018 issue.