That sunset bull

August 21, 2017

The tapestry of a leopard hunt

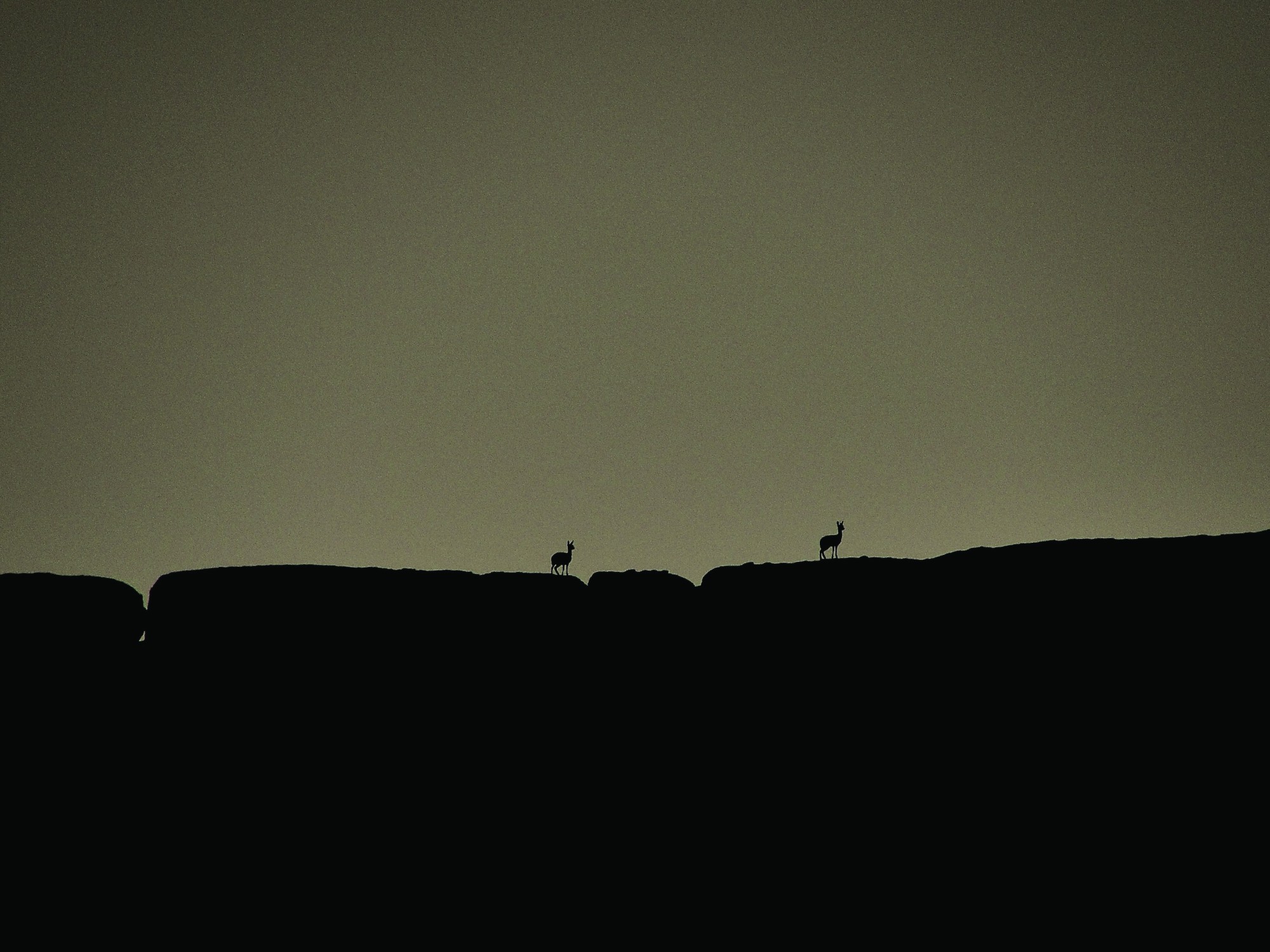

August 22, 2017K lipspringer live in pairs or in small It was the first time that I saw klipspringer so I remember an experience we had one family units, which usually consist of a male and female with one or two o spring from the previous years. Very young o spring is rarely seen because new-borns are kept hidden for up to three months to protect them – mainly against raptors.

Since klipspringer are highly territorial and rams defend their territory and family unit against intruders, even of the same species, young males have to leave and fend for themselves soon after they reach sexual maturity. They will roam about for some time until they are able to establish their own territory. Territories – which can be quite small in densely populated habitats – are marked by ‘communal toilets’, the only place where the animals will leave their droppings.

One day I hiked onto our ‘plateau’ with my uncle and aunt. We sat near the edge of the rugged plateau in the warm afternoon sun and looked down into a basin-shaped valley. A dry riverbed runs through it and next to it is a small plain with sparse grass.

We had noticed two young kudu bulls on the little clearing as we sat down. Soon afterwards two klipspringer arrived. Somebody once told me that klipspringer tread extremely carefully, as if on eggshells, when they are not on hard ground, but that was not the case. They moved onto the sandy clearing totally at ease.

It was the first time that I saw a klipspringer so calm and completely relaxed, with the kudu next to them appearing oversized. Even when the kudu started to fight, the klipspringer seemed unfazed and continued to feed on some plants on the ground. After a while they disappeared between the granite boulders on the other side of the valley.

Incidents like these are unusual when hunting for klipspringer. These antelope have keen eyes and they are extremely vigilant. Usually you become aware of them only when you hear their typical whistling alarm call, which warns the entire area as well. And even then you may still not see them at all. Due to their peculiar granite-like colouring, klipspringer are very difficult to spot. What is more, they tend to look out from elevated places where they stand motionless as if rooted to the ground for what feels like an eternity. In order to catch sight of this graceful antelope you often have to scan the surroundings with your binoculars for a long time, to even then probably see them only far away.

The most impressive characteristic of these small antelopes, however, is the way in which they move about in such rugged, difficult terrain.

With what breath-taking speed and unwavering trust in their own skills they move around in their mountainous granite world! I remember an experience we had one afternoon in the Erongo Mountains. It was in an intricate broken area of granite rocks, millions of years old, interspersed with dense thorny vegetation.

As we stalked across a small hilltop we heard the warning whistles of klipspringer and seconds later saw three of them flying down over a granite slab on the opposite slope. It happened so fast that all we caught sight of were some shadows in motion. Moments later the reason for the spectacular performance appeared: a leopard! He had stopped at the edge of the slab, as he clearly did not want to risk breaking his neck in pursuit of his quarry. For a few seconds he stood gazing after the whistling klipspringer, and then – unsuccessful this time – retreated across the granite slab. The klipspringer continued to whistle for a while, but soon calmed down again.

Even today I wonder how they managed to come down the slope safely at such breakneck speed. It was utterly impressive.

Whenever I see klipspringer I feel as if I were watching a ballet staged by nature. With seemingly stiff legs they gracefully move through the most challenging terrain on tiptoe, jump across deep crevices or stand at the steepest precipice – and all of it in the trusting and perfectly natural manner that you only find in animals.

Klipspringer can be encountered everywhere, on small granite ridges as much as in the highest mountain ranges. The hooves of klipspringer are quite unique. They resemble hard rubber and over time have evolved in such a way that the animals walk on the tips, which gives them incredible grip and support. Since they easily find footholds in the most unlikely places they can be seen at the most daring spots where even the king of the mountain world, the greater kudu, does not venture. Klipspringer enjoy boundless freedom and do not have many natural enemies other than the stealthy leopard, whose main quarry they are, and the master of the skies, the Verreaux’s eagle. Deep gorges may also be their undoing. But even then Mother Nature has provided for them: the hair in the coat of klipspringer sits loosely in the follicles so that a leopard or bird of prey can ‘slip o ’ with just a tuft of fur in its claws. Furthermore the hair is hollow inside like a small tube, which helps absorb the impact of a fall and insulates against chilly conditions at high altitudes in mountainous regions.

All these characteristics – the sharp eyes, the incredible agility and adaptation to the terrain – make the klipspringer a highly attractive quarry to another natural enemy: man.

While a hunting trip to Namibia ‘just’ for a klipspringer is perhaps not all that worthwhile, the klipspringer hunt can well be combined with a hunt for greater kudu or leopard – both of them share the habitat with the klipspringer.

A lot of patience and perseverance is necessary for a klipspringer hunt. Early in the morning an elevated observation point should be found to scan the surroundings with binoculars. is should be done with extreme thoroughness. Klipspringer usually bask in the first sunlight, especially after cold winter nights. At that time of day they are easier to find, but they vigilantly watch out themselves. As soon as they have been spotted one should try and identify a ram. High resolution binoculars, or better still a spotting scope, would seem helpful, but once the granite heats up one won’t be able to distinguish much because of distortions in the shimmering heat.

The first step should be to identify a male. If the distance makes further identification impossible it’s time to start stalking. It should always be kept in mind that klipspringer are extremely vigilant. Therefore cover should be used at all times. Every so often one will have to skirt large areas to avoid being noticed. The rather inaccessible terrain makes stalking all the more di cult, but on the other hand provides good cover. All things considered it is a strenuous a air!

Once you are a little closer to the game you should try to estimate the ram’s age. A sturdy, well-shaped body is the first indication of a fully grown, mature klipspringer. e best tell-tale characteristic for age, however, are the horns. Klipspringer have relatively smooth, straight horns which more or less match the height of the ears. e horns of mature males are finely ribbed at the base while those of young males are smooth. Old males past their prime show another burst of growth, which can be up to 2-3 cm in big rams. e ribbed part of the horn is pushed up by the secondary growth spurt and forms a visible bulge. With increasing age horns also show wear and tear: the tips are no longer sharp and the ribbing becomes blurred from rubbing on vegetation.

If you have found a male like that, the stalk has been worth your while.

But if the ram is too young, or has been lost, the hunt continues. In the case of old territorial males one can concentrate on the same area by patiently scanning it in the morning and afternoon. ere is no point in stalking at midday because klipspringer will then stand in the shade somewhere and will be even more difficult to spot.

Nowadays the latest technology makes it possible to bag klipspringer from an unrealistic distance, but in my opinion this has little to do with hunting.

A hunter should always do justice to his quarry and try to outsmart it despite its finesse.

Technology should only be roped in to spot a klipspringer and identify its characteristics as far as possible.

Most importantly, however, the klipspringer’s freedom should be felt – look from the highest elevations into the deepest gorges, let your eyes roam into the distance, scramble through seemingly insurmountable terrain and every now and then experience the hair- raising fear of falling. All of this is part of stalking a klipspringer.

When you have experienced this, and perhaps were in fact lucky enough to take an old klipspringer in some lonely heights, you will know that you managed to bag a maybe not ‘royal’, yet iconic game animal of the African mountainscape.

This article was first published in the HuntiNamibia 2017 issue.